by M. Nathalie Hristov, MLIS

Professor and Music Librarian

University of Tennessee

Kathryn A. Linton

Music Librarian for Instruction and Outreach

Vanderbilt University

Joshua Ortiz Baco

Assistant Professor and Digital Scholarship Librarian

University of Tennessee

1. Impetus for the Development of Emerging Digital Tools and Technology for Musicological Research and Pedagogy

Currently, traditional scholarly resources enable musicologists to trace the origins of numerous musical systems, styles, and instruments through the painstaking process of wading through physical volumes from several world regions to find commonalities. While there has been a significant rise in the digitization of music archives, the content represents only a small fraction of the vast collections of historical documents related to music in libraries across the globe.[1] Furthermore, digital collections in music are stored differently among thousands of libraries with their own unique set of finding aids and organizational structure. Considering the limited amount and fragmented nature of digitized historical documents in music, the time-intensive process of extracting content from multiple sources poses challenges for researchers looking for connections between musicians and musical ideas. Thus, major discoveries in musicological research are few and far between when compared to those in other disciplines. In a variety of ways, music scholarship has lagged in terms of digitized resources and technological innovations. [2] Nevertheless, music scholars and digital humanists in the last couple of decades have begun exploring methods for moving musical research forward into the technological era with greater global access and emerging technologies.[3]

In a 2023 summary of the state of digital scholarship in music, Anna Kijas alludes to the significance of a digital scholarship services model introduced by Jennifer Vinopal and Monica McCormick in 2013.[4] The Vinopal and McCormick model represents levels of library participation in the mediation and development of digital tools, offering multiple “entry points” for librarians to engage in this type of work. Using this model to consider an appropriate role for libraries to engage in digital scholarship, different tiers illustrate levels of engagement ranging from wikis, blogs, and scanning services in the lower levels, to custom-designed user interfaces and grant-funded, first-of-its-kind, research and development work in the upper echelons.[5] To reach these higher levels of digital scholarship described by Vinopal and McCormick, music librarians must take a leading role in the development of technological innovations that exist in other disciplines, in the pursuit of the next major historical discovery. Furthermore, librarians, musicologists, digital humanities experts, and computer scientists must work together to create digital tools that represent the authoritative standards and criteria set by music librarians.

In the last several years, music librarians have discussed and documented the need for greater access to digital scholarly resources in musicology.4 “Music document collections are an important part of the world cultural heritage. Digitization of these collections is essential for ensuring their preservation and future access in searchable digital music libraries.”[6] Researchers are not only challenged by a lack of digital content in terms of musical scores and manuscripts, but also by the absence of a platform that would facilitate the controlled digital lending of musical scores by libraries. While providers such as Nkoda, Classical Music Library (ASP), Henle Digital Library, and others provide subscription access to licensed musical scores, these collections represent a small fraction of the volumes of notated music that has been produced throughout the centuries. All things considered, without extensive efforts to digitize musical sources and input extracted/transcribed data from each, even the application of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence offer little to music researchers when reliable data sources simply do not exist.

Beyond the development of digital content is the visualization of the data represented in the content to determine intersections between musical ideas and persons. There are numerous examples demonstrating the value of visualization tools in historical research and pedagogy. Beyond their use as illustrations or representations of data, interactive visualizations can function as interfaces for exploratory analysis and search interfaces that facilitate discovery and research.[7][8][9] Although visual search and visualizations are increasingly employed in humanities projects broadly, they have yet to gain significant traction in the fields of musicology, music education, and music librarianship. Given their expertise in digital literacy, data management, and the latest digital tools, music librarians and information specialists are uniquely positioned to support and collaborate with musicologists, music educators, and students to incorporate more up-to-date teaching and research methods that align with the evolving needs of modern universities and the broader landscape of musicology.

Addressing the technological challenges to research and exploration by music scholars, a team of librarians at the University of Tennessee sought to design and create an innovative and valuable resource that would facilitate research on the origins and migration of music and musical ideas across time and space using GIS platforms, as well as a timeline function to visualize historical progressions. Ultimately, this project team endeavors to engage a worldwide network of librarians and music historians to populate the resources’ data sets using authoritative sources from their own collections and archives while applying controlled vocabulary standards for global participation. Ideally, the resulting digital tool would provide open access to content.

Prior to engaging in this work, the librarians needed to perform an extensive review of similar platforms in other disciplines to illustrate the potential benefits to the future of musicological research and study, as well as to select features from each that could help optimize music research and discovery. Ultimately, the project proposed by this team of librarians and information architects drew inspiration from ambitious efforts like these which have made significant contributions in history, political science, sociology, digital humanities, and literature. A similar resource for the study of music and musical ideas can have wide-ranging implications for musicologists, music teachers, and students. The following assessment of selected projects with the closest similarities to what the UT taskforce conceived illustrates the benefits of the visualizations offered while addressing the limitations of each.

2. Review of Existing Digital Tools for Historical Research and Discovery

Perhaps the most recognizable visual exploratory data project in digital humanities, the now multinational Mapping the Republic of Letters (2017), capitalizes on the wealth of metadata created from archival sources and visualized as maps, networks, and plots. The project proposes visualizations as a method to interrogate established notions of North American and European intellectual networks.[10] The project’s case studies have primarily centered on historical figures and groups. The project’s team proposes that these graphical illustrations are: “employ[ing] computational technologies and visualization techniques to make discoveries about the past that would have been difficult, if not impossible, to reach by analog means.”[11]

Figure 1. Map and graph visualizations from the Mapping the Republic of Letters case study “Voltaire’s Correspondence Network” displaying 1,897 data points illustrating geolocation and language of the correspondences.

Figure 1. Map and graph visualizations from the Mapping the Republic of Letters case study “Voltaire’s Correspondence Network” displaying 1,897 data points illustrating geolocation and language of the correspondences.

Figure 2. Network graph of the Six Degrees of Francis Bacon project showing over 4,000 data points and the user contribution feature.

Figure 2. Network graph of the Six Degrees of Francis Bacon project showing over 4,000 data points and the user contribution feature.

Six Degrees of Francis Bacon is a project hosted by Carnegie Mellon University Libraries which explores Britain’s early modern social network.[12] SDFB follows a different approach to sources and visualizations by using data extracted from biographies in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[13] Whereas the Mapping the Republic of Letters takes advantage of neatly organized information about each letter and sender, the team from Six Degrees of Francis Bacon utilizes statistical inference to detect connections between people. This larger scale serves as a “workable infrastructure” that can be “corrected and expanded to encompass the interests of a wide range of humanist scholars,” which the project expects would lead to “the integration, or re-integration, of disparate threads”[14]

Another example that illustrates the significance of visualization in facilitating important historical discoveries comes from a collaboration between historians in one part of the world and a team of digital humanities scholars in a different part of the world. In 2020, a team of Czech historians analyzed the relationship between the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) and his correspondents in Bohemia and elsewhere in Central Europe.[15] This team used Palladio[16], a data-driven tool for analyzing relationships across time to analyze data from Kircher’s correspondence.[17] Using Palladio to help visualize the migration of these letters, the Czech team discovered a remarkable number of letters that had been sent from Bohemia. Without Palladio, the authors attest that the work to trace the migration of the correspondents would have proven much more difficult and may have prevented the discovery of key letters.[18]

Figure 3. Visualization of letters to Kircher from Europe, 1633-1680, created by Nicole Coleman, Humanities + Design, Stanford University. The size of the dots corresponds with the number of letters in each city. This image was published in Iva Lelková, Paula Findlen, and Suzanne Sutherland, “Kircher’s Bohemia: Jesuit Networks and Habsburg Patronage in the Seventeenth Century,” Erudition and the Republic of Letters 5, no. 2 (2020): p. 174. (Image used with permission of the copyright owner.)

Figure 3. Visualization of letters to Kircher from Europe, 1633-1680, created by Nicole Coleman, Humanities + Design, Stanford University. The size of the dots corresponds with the number of letters in each city. This image was published in Iva Lelková, Paula Findlen, and Suzanne Sutherland, “Kircher’s Bohemia: Jesuit Networks and Habsburg Patronage in the Seventeenth Century,” Erudition and the Republic of Letters 5, no. 2 (2020): p. 174. (Image used with permission of the copyright owner.)

Another resource offering a timeline and map of Medieval Philosophers uses the TimeMapper platform. The data source for this tool is listed as Wikipedia. While there are overlaps of historical figures in the timeline, the inability to map physical intersections is a limitation of the platform. Additionally, using Wikipedia as a data source precludes validation by librarians. Ideally, a resource of this nature should be populated by primary sources (whenever possible) that could be digitally examined through the portal.

Figure 4. Medieval Philosophers using Open Knowledge Foundation Labs platform TimeMapper, https://timemapper.okfnlabs.org/okfn/medieval-philosophers#1 .

Figure 4. Medieval Philosophers using Open Knowledge Foundation Labs platform TimeMapper, https://timemapper.okfnlabs.org/okfn/medieval-philosophers#1 .

The proposed project from the University of Tennessee draws inspiration from ambitious efforts like these which have made significant contributions in history, political science, sociology, digital humanities, and literature. A similar resource for the study of music and musical ideas can have wide-ranging implications for musicologists, music teachers, and students.

3. A Selection of Online Digital Tools for Music Study and Research

The Geographical View of Chopin’s Musical Influences (2019, no longer active) produced a single case study of one historical figure, Frederic Chopin, and drew its data from an academic publication to generate the spatial representation and contextual information for the project.[19] Unfortunately, work on this project has not resumed and the author lamented that, “with a greater duration for the project, footsteps of multiple composers could be depicted, establishing the influence one composer had on another. This would clearly show the dissemination of ideas and interconnectedness of the music world, giving users a better understanding of how music evolved throughout the years.”[20] Additionally, the author expressed numerous challenges in populating data sets from authorized sources. While there are unverified sources of data throughout the internet, the authors conceded that the “reliability of the sources must be taken into account.”[21] This is where librarians can play an essential role in using the development of data sets using authorized records and primary source materials.

Figure 5. Chopin StoryMap created with ArcGIS Desktop. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/824e697e-3c8b-4d5e-b74a-921cad3a12f4/content

Figure 5. Chopin StoryMap created with ArcGIS Desktop. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/824e697e-3c8b-4d5e-b74a-921cad3a12f4/content

Other projects related to music history utilize the proprietary, subscription-based presentation and mapping platform, ArcGIS StoryMaps.[22] Using StoryMaps, the Musical Geography Project (2015) hosts case studies of musicians, groups, and institutions with a focus on spatial-based storytelling in music history.[23]

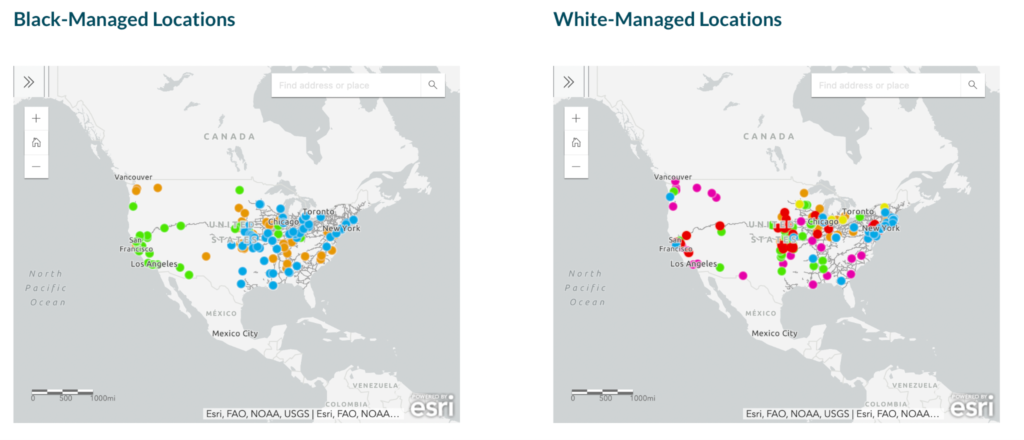

Figure 6. These maps created through the Musical Geography Project (2015) show where Black minstrel troupes performed from 1871 until 1939.

Figure 6. These maps created through the Musical Geography Project (2015) show where Black minstrel troupes performed from 1871 until 1939.

Common approaches for projects like the one proposed at the University of Tennessee use free or open-source platforms, like Omeka and Google’s MyMaps. Documenting Teresa Carreño created by Anna Kijas, music librarian in Tufts University, collected and described documents of Carreño’s performances, which are hosted on an Omeka site together with an interactive map of the geolocated performances of the singer.

Figure 7. Map representation from Documenting Teresa Carreño of the location of primary sources related to her life and work.

Figure 7. Map representation from Documenting Teresa Carreño of the location of primary sources related to her life and work.

Similarly, Sakira Ventura used MyMaps for her Global Map of Women which incorporates national origin, portraits, and biographical information of women musicians using sources such as Wikipedia, YouTube, or Spotify. A limitation of this platform, other than the veracity of the data sources used, is that it is unable to generate information that shows connections or intersections between two subject matters.

Figure 8. This Global Map of Women created by Sakira Ventura represents important information and visuals for notable women composers, but it relies on unverified sources such as Wikipedia and commercial platforms (eg. YouTube or Spotify) for streamed audio and video.

Figure 8. This Global Map of Women created by Sakira Ventura represents important information and visuals for notable women composers, but it relies on unverified sources such as Wikipedia and commercial platforms (eg. YouTube or Spotify) for streamed audio and video.

Documenting Teresa Carreño and Global Map of Women are well-designed online tools, both serving as reference resources for specific topics with information parsed from archival sources or crowd-sourced information, respectively.

Larger projects in music history have also created bespoke platforms that serve as research and reference tools for educators and researchers. For example, Patrick Galbraith’s Map of Metal (https://mapofmetal.com/) traces the history of heavy metal subgenres with recordings to represent the distinct styles, while the NEH funded Global Jukebox (2010) project contains folk and indigenous music recordings which have been described and annotated by musical style, point of origin, and geographic spread. Global Jukebox specifically provides interactive maps that can be navigated by cultures, nations, or musical style, and educational materials like lesson plans and presentation slides.

Figure 9. The NEH funded Global Jukebox allows users to discover the origins of folk and indigenous music, mapping its dissemination across space. In addition to the visual representation of the migration of this music, audio recordings of the music described are accessible for streaming. Association for Cultural Equity. “The Global Jukebox.” Accessed May 4, 2023. https://theglobaljukebox.org/

Figure 9. The NEH funded Global Jukebox allows users to discover the origins of folk and indigenous music, mapping its dissemination across space. In addition to the visual representation of the migration of this music, audio recordings of the music described are accessible for streaming. Association for Cultural Equity. “The Global Jukebox.” Accessed May 4, 2023. https://theglobaljukebox.org/

Like the project proposed in this paper, these examples draw from multiple sources and demonstrate the relationship between music and geography. The UT Musical Maps project builds on the audiences and expertise of these resources by adding a broader approach to music history that goes beyond the limits of the case study models (Geographical, Documenting, Global Map) or single organizing category (Global). While these projects demonstrate that there are multiple audiences and potential collaborators, librarians from the University of Tennessee proposed the development of a system that would make unique and innovative contributions by expanding the focus on Western music, utilizing controlled vocabularies and facet searching, and a structured and standardized input form for entries.

4. The University of Tennessee Musical Maps Project

After consulting with several experts in software development at the University of Tennessee and Saint Louis University, it was determined that no platform currently exists to create the types of visual, query-generated output that would allow researchers to visualize multiple subjects simultaneously and analyze the overlaps in music and musical ideas. To realize such an objective, a new tool would have to be developed from scratch. Since the creation of such a utility would require a great deal of funding and investment of time, a small scale, production-type model was developed that would demonstrate the possibilities for a powerful utility where the design would incorporate the expertise of music librarians, public services libraries, and digital humanities librarians. Important elements of the design would include a data dictionary of controlled vocabulary and content designators, a clear hierarchy of relationships, and a data set that would allow for the establishment of related entities.

Guiding Principles for the Development of a Musical Map

Figure 10. Guiding Principles for the development of the UT Musical Map.

Figure 10. Guiding Principles for the development of the UT Musical Map.

The first step was to establish guiding principles for the project design. These principles include data sets generated by librarians using primary sources from collections; controlled vocabularies, standardized descriptions, facet filtering to optimize “precision and recall,” and the ability to generate meaningful output that visually represents music history in a way that facilitates the discovery of historical connections. For the first principle, the project team determined that in the initial stage, primary sources from library archives would be used whenever possible to populate the data sets. Using data from primary sources lends authority to the output of the digital tool, although secondary sources may be used from librarian-trusted materials when necessary. For controlled vocabularies, the team opted to use Library of Congress name authority records for personal/corporate names, and topical subject headings in combination with wikidata fields for entering instruments and events. To standardize the description of data, the subject specialists created a data dictionary of content designators. Finally, the team conducted an environmental scan of recent work on best practices for visualization, search, and presentation design in the digital humanities.

At this stage, primary sources from the University of Tennessee Libraries Special Collections were used to populate the data sets for the prototype. In this example of a handwritten program by Gottfried Galston, the content was transcribed to extract information on his cycle of over 40 recitals and concerts in Munich dating from October 1919 to February 1921. This original handwritten program resides in the Galston-Busoni Archives of the University of Tennessee Libraries Special Collections. An image with the primary source is also included in the entry.

Figure 11. This handwritten program by Gottfried Galston resides in the Galston-Busoni Archives of the University of Tennessee Libraries Special Collection. The program was used to populate the data set of the UT Musical Maps prototype.

Figure 11. This handwritten program by Gottfried Galston resides in the Galston-Busoni Archives of the University of Tennessee Libraries Special Collection. The program was used to populate the data set of the UT Musical Maps prototype.

To populate the data set, internal and external library technologists created a data entry form that allows for hierarchical data to be entered and organized (see Appendix 1). The data dictionary defined designators for the different types of events, people, places, and things that populated the data sets (see Appendix 2). So, the digital tool envisioned was developed by assessing existing platforms with some of the desired functionality of the prototype, incorporating those elements into the design.

This following image contains an example of how the data is structured using controlled vocabulary from Library of Congress authority records and wikidata elements. Additionally, the GeoNames[24] to enter the spatial information of our events. GeoName provides latitude and longitude for existing places and landmarks.

Figure 12. Data structures using controlled vocabularies.

Figure 12. Data structures using controlled vocabularies.

The most impactful and immediate contribution of the form and the data dictionary is the creation of records as linked open data which can be incorporated into international efforts in cultural heritage organizations like, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums, that already freely provide access to large repositories of data in interoperable formats[25]. The use of linked open data means that this project is not limited to the work of one group of librarians and that anyone with the interest and knowhow in music and metadata can contribute and expand what this prototype does.

In terms of meaningful output, David McCandless’s Information is Beautiful contends that any successful visualization of data should contain reliable information, tell a story, represent specific goals, and do this with elements organized visually.[26] This served as the UT team’s inspiration to create graphical representations that made arguments or scholarly debates explicitly while leaving room for curiosity and discussion. Figure 13. David McCandless’s, “What Makes a Good Visualization?” from Information is Beautiful, London: Collins, 2009. (Image used with permission of the copyright owner.)

Figure 13. David McCandless’s, “What Makes a Good Visualization?” from Information is Beautiful, London: Collins, 2009. (Image used with permission of the copyright owner.)

The project team at UT is continually revisiting how the composition and organization of the different elements in a visualization can make design and scholarly choices as transparent as possible. One of the primary challenges of ethical information visualization is incorporating and revealing UX and UI decisions so that end users can become active participants in meaning-making. By supporting meaning-making, the goal is an interface that invites exploration and creation rather than just closed or preset representations of information. So, the team at the University of Tennessee wanted to develop a resource that has it all: quality data derived from primary sources when possible, controlled vocabularies, standardized descriptions, linked open data, remediation when needed, and meaningful output that is engaging, informative, and accessible. In consultation with colleagues in Digital Initiatives, Mark Baggett and Meredith Hale, the team identified the wide range of technical expertise and partners that would be required to implement all these goals and specific design concepts.

In the Spring of 2023, after receiving seed funding from the University of Tennessee Libraries, a team of IT Architects and Developers from Saint Louis University were contracted to bring the Musical Map project to fruition. This team led by Patrick Cuba and Bryan Haberberger had years of experience developing platforms for digital humanities projects throughout the United States. Several of the projects they have worked on employ search facets we wanted to incorporate in our own project, so some of the coding from previous projects could be reproduced. The search facets work like filters to more effectively search through information, and they were selected by the subject specialists in music using the metadata fields from Wikidata. With the team from Saint Louis, the project team at the University of Tennessee explored a multitude of open access software and existing utilities to determine what could be used and what would need to be developed from scratch to meet the parameters for the data sets, controlled vocabularies, descriptors, and output needed for use by researchers, pedagogues, practitioners, and students.

The following image represents the output generated using the data entered in the prototype. As evidenced by this image, the record generated for a specific subject includes a list of events, primary source documents, and related individuals and/or topics. The data are interconnected across materials like images, maps, paper documents, text transcriptions, and metadata, as well as linked to other objects in the project through linked data in each element.  Figure 14: Displays mock-up created by Patrick Cuba and Bryan Haberberger in collaboration with M. Nathalie Hristov and Kathryn Linton to represent a person record, Gottfried Galston. This mock-up shows events with documents of evidence. Additionally, the image shows related people and connections that Gottfried Galston has based on the data entered.

Figure 14: Displays mock-up created by Patrick Cuba and Bryan Haberberger in collaboration with M. Nathalie Hristov and Kathryn Linton to represent a person record, Gottfried Galston. This mock-up shows events with documents of evidence. Additionally, the image shows related people and connections that Gottfried Galston has based on the data entered.

Furthermore, connections are not limited to the relationships between two or more individuals, but could be represented by a place or thing, such as a specific musical landmark and the persons associated with the landmark. Future phases of the project are expected to permit multiple timelines to be overlaid geographically and chronologically allowing researchers to identify intersections in the timelines for further exploration.

Ultimately, the development of these musical maps should generate the following outcomes:

- A reliable source for scholarly research and the study of music and musicians throughout time and space;

- Librarian oversight to ensure the integrity and authority of the data, as well as the precision and recall of queries;

- Visual output generated from user queries is optimized to meet the learning style of contemporary and future students and scholars.;

- Connections between musical entities that are more easily discerned through computer generated comparisons.

As mentioned, the University of Tennessee Musical Maps project is in the early stages of development. Currently, the process of entering data derived from primary source materials is limited to the University of Tennessee’s Galston-Busoni Archives. As the functionality of this digital tool is developed by optimizing the output that visualizes the timelines of both Galston and Busoni, the project team at the University of Tennessee invites music librarians and archivists to collaborate on the project by helping to populate global data sets. The image below represents a future iteration of the musical map with intersecting timelines.  Figure 15: Displays mock-up created by Patrick Cuba and Bryan Haberberger in collaboration with M. Nathalie Hristov and Kathryn Linton to represent the interactive musical map including the timeline function at the bottom of the screen to expand or narrow results based on year and an option to choose a timeline of people. Things and places will be included in future iterations of the musical map.

Figure 15: Displays mock-up created by Patrick Cuba and Bryan Haberberger in collaboration with M. Nathalie Hristov and Kathryn Linton to represent the interactive musical map including the timeline function at the bottom of the screen to expand or narrow results based on year and an option to choose a timeline of people. Things and places will be included in future iterations of the musical map.

Next Steps in the Development of a Musical Map

In 2024, financial constraints and shifting organizational priorities have hindered progress towards the realization of the University of Tennessee Music Maps project. In addition to the technical development of the utility, dedicated server space and fast processors to handle complex queries linking multiple data sources would be required, as well as dedicated staff to maintain and update the system. Additionally, the cooperation of a global network of music librarians would be required to populate the data sets with primary source materials and data from their own collections. Despite these challenges, the prototype developed over the last year has served as an opportunity to identify the best data sources for populating the records (e.g., GeoNames, LC Authority Records, primary sources from library archives), controlled vocabulary, search facets, and output standards for optimal research and pedagogical value. Furthermore, librarian oversight of such a powerful research tool would nearly guarantee the authority of generated results.

The team of librarians who designed the project recognize that such a utility must exist in order to advance the study of music and music history. However, they also recognize that there is no compelling reason for keeping the project at the University of Tennessee. Using best practices and guidelines established in this paper, the team would be willing to work with interested library professionals with the capacity to overcome these institutional challenges towards the development of a powerful research tool for the advancement of musical studies.

References

Davis, Edie, and Bahareh Heravi. 2021. “Linked Data and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of Participation, Collaboration, and Motivation.” J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 14 (2): 21:1-21:18, https://doi.org/10.1145/3429458

Duguid, Timothy. “Behind the Times? Digital Research Methods and the Music Classroom.” Notes (Music Library Association) 77, no. 4 (2021): 519-538, https://doi.org/10.1353/not.2021.0037

Edelstein, Dan, et al. “Historical Research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project.” The American Historical Review, vol. 122, no. 2, Apr. 2017, pp. 400–24. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.2.400

Kijas, Anna. “Documenting Teresa Carreño.” Accessed May 2023. https://documentingcarreno.org/

Lelková, Iva, Paula Findlen, and Suzanne Sutherland. “Kircher’s Bohemia: Jesuit Networks and Habsburg Patronage in the Seventeenth Century.” Erudition & the Republic of Letters 5, no. 2 (April 2020): 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1163/24055069-00502002

McCandless, David. Information is Beautiful. London: Collins, 2009.

St. Olaf College. “The Musical Geography Project.” Accessed May 4, 2023. https://musicalgeography.org/.

Ufer, Nikolai, Max Simon, Sabine Lang, and Björn Ommer. “Large-Scale Interactive Retrieval in Art Collections Using Multi-Style Feature Aggregation.” PLOS ONE 16, no. 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259718

Urberg, Michelle. “Pasts and Futures of Digital Humanities in Musicology: Moving Towards a ‘Bigger Tent.’” Music Reference Services Quarterly 20, no. 3-4 (2017): 134-150, https://doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2017.1404301

Ventura, Sakira. “Global Map of Women.” Accessed May 4, 2023. https://svmusicology.com/mapa?lang=es.

Vinopal, Jennifer, and Monica McCormick. “Supporting Digital Scholarship in Research Libraries: Scalability and Sustainability.” Journal of Library Administration 53, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.756689

Wood, Anna L., Kathryn R. Kirby, Carol R. Ember, Stella Silbert, Sam Passmore, Hideo Daikoku, John McBride, et al. “The Global Jukebox: A Public Database of Performing Arts and Culture.” PLOS ONE 17, no. 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275469

APPENDIX 1

Musical Map Data Entry Form Creation Outline

Events

Creator id

Ex. Shepas_TKN

Type of event (DATA DICTIONARY) (Repeatable)

Ex. Birth

Associated with personal, corporate, or meeting name (LOC NAR): (Repeatable)

Ex. Galston, Gottfried, 1879-1950

Place of event (GeoNames)

Ex. Peregringasse, Vienna

(latitude and longitude from GeoNames)

Associated with (thing) Name from LCSH topical subject heading or LC Name Title Authority Record (Repeatable)

Date of event (yyyy/mm/dd with drop down calendar)

Ex. 1879/08/31

Range date

Ex. 1820-1830

Reference(s):

—---------

Creator id

Ex. Shepas_TKN

Type of event (DATA DICTIONARY) (Repeatable)

Ex. Performance

Associate personal, corporate, or meeting name: (Repeatable)

Ex. Galston, Gottfried, 1879-1950

Place of event (GeoNames)

Ex. Gewandhaus (Leipzig, Germany)

Lat: 51.3378

Long: 12.3704

Reference(s):

Associated with (thing) [Name from LCSH topical subject heading or LC Name Title Authority Record] (Repeatable)

Reference(s):

Date of event (yyyy/mm/dd with drop down calendar)

Ex. 1879/08/31

Reference(s):

Date range

Ex. 1820-1830

Reference(s):

—------

People

Creator id

Ex. Shepas_TKN

Name from authority record (LC-NAR)

Ex. Galston, Gottfried, 1879-1950

NAR: https://lccn.loc.gov/n79011997

Name_displayed_as

Ex. Gottfried Galston

Student of (Name from authority record) (Repeatable)

Ex.Busoni, Ferruccio, 1866-1924

NAR: http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n79124601

Reference(s): Tamara Levitz, “Ferruccio Busoni and His European Circle in Berlin in the Early Weimar Republic,” Revista de Musicología, 16, no. 6 (1993): 3705-3721.

Students taught (Name from authority record) (Repeatable)

Ex. Carter-Zagorski, Patricia

NAR: https://lccn.loc.gov/no2004110865

Reference(s): Interview with Patricia Carter-Zagorski, April 15, 2021.

primary occupation(s) (controlled designators in a drop-down menu)

Ex. instrumentalist (piano)

Ex. pedagogue

References:

Ex. https://scout.lib.utk.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/176452

Notes: In UTK special collections

secondary occupation(s) (controlled designators in a drop-down menu) (Repeatable)

Ex. composer

Reference(s):

Instrument (s) (topical LCSH (Repeatable)

Ex. piano

Reference(s):

Vocal Range (controlled designators in a drop-down menu (Repeatable)

Ex. Baritone

Place (musical landmarks)

Creator id

Place Name: Gewandhaus (Leipzig, Germany) (GeoNames)

Lat:

Long:

Primary function (could have multiple primary functions: examples, performance venue, music education facility, etc.; Repeatable)

Ex. Performance Venue

Secondary function (could have multiple secondary functions: examples, performance venue, music education facility, etc.; Repeatable)

Ex. Music Education Facility

Things

Creator id

Name from LCSH topical subject heading or LC Name Title Authority Record

Ex. URI: http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/no98006721

Work: An die Jugend, Preludietto, Fughetta ed Esercizion, No. 1, (393)

Reference(s):

Image upload

Precursor (Repeatable)

Image upload

Successor (Repeatable)

Image upload

Reference(s):

Notes:

Annotation

Record:

Ex: [Main entry from parent record]

Image upload

Ex. Sound file (link)

APPENDIX 2

Dictionary of Content Designators – Digital Music Map

| Facets (people, places, and things) | |

| Events | |

| Birth | |

| Death | |

| Studied in / Educated in | |

| Taught at | |

| Performed in | |

| Worked at (non-teaching or performance) | |

| Resided in | |

| Composed | |

| Created | |

| Arranged | |

| Modified | |

| Edited | |

| Established | |

| Ceased | |

| Reestablished | |

| Visited | |

| Renamed (GeoNames data) | |

| Places (Musical Landmarks) | born_in_city ; born_in_place ; died_in_city ; died_in_place ; orginated_in |

| Performance venue | performed_in ; primarily_functions_as ; secondarily_functions_as |

| Residence | primarily_functions_as ; secondarily_functions_as ; born_in_place ; died_in_city ; died_in_place |

| Ex. Home | |

| Ex. Where a composer wrote a specific piece | |

| Music education facility | studied_in ; primarily_functions_as ; secondarily_functions_as |

| Place of musical subject | |

| Example the Moldau River | |

| Things | |

| Musical event (ceremony) | |

| Musical work | |

| Ex. includes all religious ceremonies | |

| Musical event (performance series, festival) | musical_events_hosted_in |

| Musical event (performance series, competition) | musical_events_hosted_in |

| Musical event (performance series, general) | musical_events_hosted_in |

| Ex. includes chamber music series any type of performance series | |

| Instrument(s) | functions_as ; precursors_of |

| Instrument family | |

| Ensemble type | belongs_in |

| Sonorities: scale / modal systems | functions_as |

| Notational systems | functions_as |

| Meters/Rhythmic patterns | functions_as |

| Styles/genres | |

| Ex. expressionist period | |

| People (general category and they could be assigned designators such as the ones below) | pedagogues_in ; students_educated_in ; teacher_of |

| Assign Designators (controlled vocabulary) | |

| Composer | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as ; teacher_of |

| Arranger | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as |

| Performer | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as |

| Instrumentalist (name of instrument) | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as |

| Vocalist (name of range) | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as |

| Conductor | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as |

| Performance Ensemble | primarily_known_as; secondarily_known_as ; ensembles_residing_in ; |

| Theorist | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Historian | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Pedagogues | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Musical collaborator (lyricist) | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Musical collaborator (arranger) | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Musical collaborator (other) | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

| Instrument maker | primarily_known_as ; secondarily_known_as |

Notes

[1] One example of a backlog in the digitization of musical sources was shared during a 2023 presentation of the International Association of Music Libraries Congress in Cambridge (UK). At the congress, Head of the British Library’s Music Collection Dr, Sandra Tuppen reported that only about 12% of the library’s 13K+ volumes of music manuscripts are digitized (excludes uncatalogued items), and that only 1.2% of their 1.5 million + items of printed music are digitized.

[2] Timothy Duguid, “Behind the Times? Digital Research Methods and the Music Classroom,” Notes (Music Library Association) 77, no. 4 (2021): 519-538, https://doi.org/10.1353/not.2021.0037

[3] Anna Kijas, “Digital scholarship,” Notes (September 2023), 40-49.

[4] Kijas, 49.

[5] Jennifer Vinopal and Monica McCormick, “Supporting Digital Scholarship in Research Libraries: Scalability and Sustainability.” Journal of Library Administration 53, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.756689

[6] J. Calvo-Zagaoza, G. Vigliensoni, and I. Fujinaga (2016). Document analysis for music scores via machine learning. DLfM 2016: Proceedings of the 3rd International workshop on Digital Libraries for Musicology (pp. 37-40). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2970044.2970047

[7] Nikolai Ufer et al., “Large-Scale Interactive Retrieval in Art Collections Using Multi-Style Feature Aggregation,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 11 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259718

[8] Lee, Benjamin and Trevor Owens. “Grappling with the Scale of Born-Digital Government Publications: Toward Pipelines for Processing and Searching Millions of PDFs,” International Journal of Digital Humanities (2021): https://doi.org/10.1007/s42803-022-00042-x

[9] Manovich, Lev. “What Is Visualisation?” Visual Studies, vol. 26, no. 1 (2011): https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586x.2011.548488

[10] Dan Edelstein et al., “Historical Research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project,” The American Historical Review 122, no. 2 (2017): pp. 400-424, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.2.400

[11] Ibid, 403-4.

[12] Christopher N. Warren et al., “Six Degrees of Francis Bacon: A Statistical Method for Reconstructing Large Historical Social Networks,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 10, no. 3 (July 2016).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Iva Lelková, Paula Findlen, and Suzanne Sutherland, “Kircher’s Bohemia: Jesuit Networks and Habsburg Patronage in the Seventeenth Century,” Erudition and the Republic of Letters 5, no. 2 (2020): pp. 163-206, https://doi.org/10.1163/24055069-00502002.

[16] Palladio is a data-driven tool for analyzing relationships across time. It was developed at Stanford University with funding from a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant.

[17] Lelková, et al, p. 203.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Daphne Hong and Emmanuel Stefanakis, “Geographical View of Chopin’s Musical Influences” (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary, 2019), pp. 1-9.

[20] Hong and Stefanakis, p. 8.

[21] Ibid, p. 8.

[22] ArcGIS StoryMap is a proprietary, subscription-based presentation and mapping platform.

[23] Anna L. Wood et al., “The Global Jukebox: A Public Database of Performing Arts and Culture,” PLOS ONE 17, no. 11 (February 2022), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275469.

[24] The GeoNames (https://www.geonames.org/) geographical database covers all countries and contains over eleven million place names that are available for download free of charge. GeoNames was developed by Unxos GmbH, a software development company, based in St. Gallen, Switzerland.

[25] Edie Davis and Bahareh Heravi (2021). “Linked Data and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of Participation, Collaboration, and Motivation.” J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 14 (2): 21:1-21:18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3429458.

[26] David McCandless’s, “What Makes a Good Visualization?” from Information is Beautiful, London: Collins, 2009.

One thought on “Musical Maps of the World in the 21st Century: Leveraging Librarian Expertise in the Development of Visualization Tools for Music Research and Pedagogy”