By Hunter Murphy

Engagement and Learning Librarian

duPont-Ball Library, Stetson University

Abstract

Employee competencies of all levels determine the overall functioning of an organization. In an academic library, student assistants at the front desk are responsible for understanding innumerable details regarding services, resources, and policies. The Library Oscars was created as a peer-to-peer video training initiative to engage library student employees, help them take ownership of their learning, and increase competencies. This article will examine the process at Lynn University and Stetson University libraries. Using the library assistant handbook as the basis for training in each instance, the students created videos based on specific procedures and policies. The process of creating a rubric used to grade the productions and incentives for quality productions are outlined. This paper examines the strategy to benefit the frontline student employees, librarians, and staff who participated in the process, as well as the outcomes of the initiative.

Introduction

College students working as library assistants must juggle numerous activities, both curricular and extra-curricular, in addition to contributing as employees. Rarely do these students answer more than basic reference questions—such as how to search books in the catalog—but many questions fall within the assistant’s purview. These questions include equipment loan procedures, printing and scanning, circulation loan policies for various users, computer troubleshooting, technology access in the library, and questions involving searching integrated library systems for library items.

At both Stetson University and Lynn University libraries, students split time between offering customer service at the desk and providing shelf maintenance and organization. In both cases, students needed to know the locations of the special shelving sections, such as government documents, music items, children, teens, and juvenile books, as well as course reserves, interlibrary loan items, reference books, media, and other items. These questions are in addition to those regarding opening and closing procedures, confidentiality policies, human resources-related issues for their employment, customer service responsibilities, and safety or emergency procedures.

Therefore, librarians and staff must find the most effective and efficient ways to engage employees and teach library procedures and policy as well as service delivery methods. One-on-one and group training can become boring, tedious, and repetitive for the trainer and the trainee. In both university libraries outlined in this paper, students were expected to read and acknowledge comprehension of the staff manual. The supervisors reviewed the material with each new employee. After an initial phase of training one-on-one and group training using the handbook as the basis, there were still misunderstandings and errors. The need for a further iteration became clear. We thought that an entertaining exploration of the content would help the employees better understand the library policies and procedures, and so the Library Oscars project was born, a low-cost learning and teaching initiative wherein students engaged in a peer-to-peer video training project which improved competencies and engaged all levels of the library. The Library Oscars do not replace traditional training. Rather, I created this initiative to reinforce training from the handbook. In this article, I will outline the process and results of the Library Oscars.

Literature Review

Traditional Training

In supervising student workers, a staff handbook or manual serves as the primary document from which to introduce and train employees. As Fitsimmons (2012) stated, “a good policy manual, which should include a detailed job description outlining their duties [and] a well-written set of procedures, will help by allowing new employees to learn their duties with as little time involvement from other busy staff members as possible” (p. 13). The issue confronting librarians is the number of details front-desk student employees must understand to provide high-quality service to users. As Maxey-Harris, Cross, and McFarland (2010) affirmed, student assistants “perform tasks crucial to the functioning of libraries” (p. 148). In fact, seventy-nine percent of college students view the library as the source to find “needed information” (De Rosa & OCLC, 2006, p. 74).

Library onboarding varies across ACRL-member libraries, as evidenced in Graybill, Hudson Carpenter, Offord, Piorun, and Shaffer’s 2013 study. The authors found that, although libraries have been “implementing various, and sometimes multiple, components of onboarding programs, many organizations have room to improve in bringing new employees on board” (p. 212). Additionally, library assistants must have an encyclopedic understanding of services librarians provide, from reference consultations, special collections, and other resources in order to direct users to the appropriate areas and personnel. As Whitney Berry wrote, “the amount of material they are expected to learn often works against students’ best efforts to succeed” (p. 153).

Library Training

There is a need to develop core competencies in library assistants. Robinson, Runcie, Manassi, and Mckoy-Johnson (2015) define core competencies as “the behaviours and attitudes that are extremely important to an organization. These competencies are instructive of those actions and attitudes that employees are expected to exhibit” (p. 25). Developing and strengthening core competencies takes time, particularly with new assistants at library customer service desks. Creating effective training methods will ease the burden of overworked supervisors and librarians. It can also help students buy-in to the library’s mission and culture. Cottrell and Bell (2015) emphasize that “student workers are neither trained to work in a library, nor do they carry the same ideological/emotional attachment to the library’s purpose in the same way as career librarians. This is a trait that must be developed in each new student worker over time” (p. 83).

Librarians and circulation supervisors have sought the most effective ways to both engage student workers and foster a sense of attachment to the library’s purpose, with training leading to more fulfilling work experiences for library assistants. “The goal of any training program is to increase work productivity—and as employees become more productive and efficient, they are happier and more excited about their jobs” (Quinney, Smith, & Galbraith, 2010, p. 210). In a study of Australian libraries, O’Neil & Comley (2010) considered training to be one of the highly-regarded “success factors to facilitate student employees’ success and engagement in the library workplace and for better support all round of student employees” (p. 110). Training leads to skill development and more thorough knowledge, which as Davis and Lundstrom (2011) noted, “ultimately leads to better service to the library’s patrons” (p. 339). Training staff supports strategic goals and can oftentimes signal the health and vitality of an effective library. As one university learned during a new training initiative, an important goal of innovative onboarding was to “build interpersonal relationships throughout the library and to promote a culture of fun and innovation” (Davis & Lundstrom, 2011, p. 342).

Peer Learning and Teaching Techniques

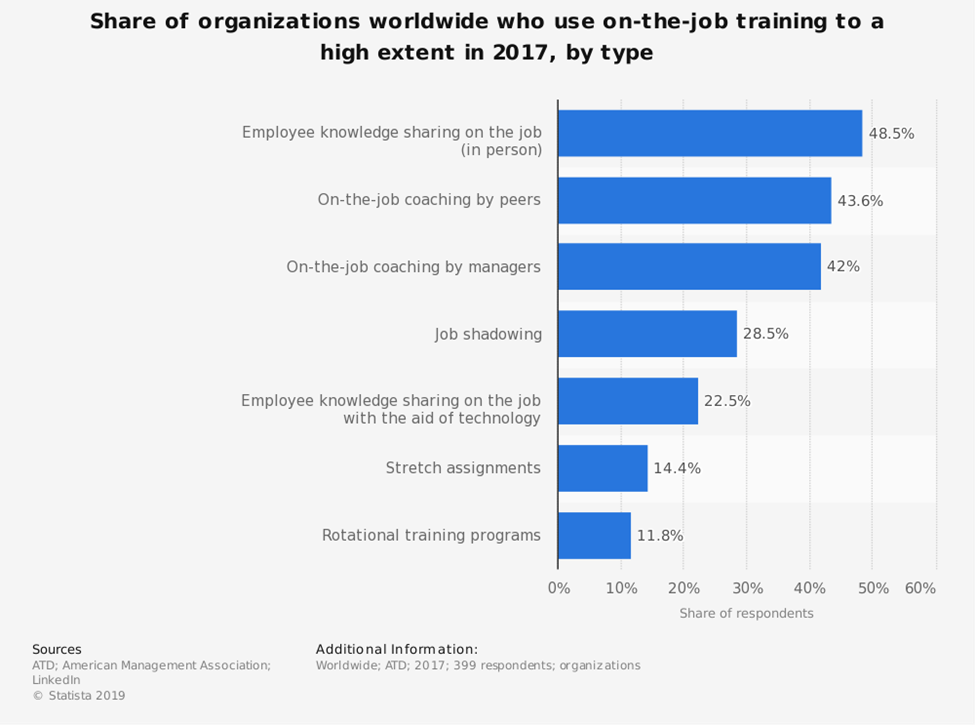

A survey from the ATD (2017) outlines how employers train their employees.

As the chart exhibits, “employee knowledge sharing on the job” accounted for the most used category among worldwide organizations in 2017 (ATD, 2017). Additionally, Figure 1 underlines how employee knowledge sharing included the use of technology a large percentage of the time. These categories suggest that peer teaching and learning are frequent components of employee training.

Research shows an effective way to learn a subject is to teach someone else about it. Klein (2003) explores the concept of docendo discimus, Latin for “learn by teaching,” which is “an old, well-established method to help students be active rather than passive participants in learning settings” (p.216). The active position gives the student and student employee a motivation to learn, but there are additional benefits to peer teaching. Klein (2003) again points out that “as students learn to put material into their own words and convey it to others, they are processing information by actively working with the material…. Peer teaching is an opportunity for a student rather than teacher-centered approach, thus students are motivated by the responsibility they now have to teach someone else” (p.216). As McCabe contends (2015), “memory can be improved when students take an active role in creating their own study materials” (p. 204). Barkley and Major (2016) would characterize the Library Oscars project as a “learning assessment technique,” because the act of the employee creating the video “provides students with an opportunity to ‘make’ something relevant to the subject area, and this allows them to construct their own knowledge as they construct the project” (p. 196). This process of mastering knowledge and synthesizing it into digital form will “deepen that learning through the act of creation” (p. 196).

Finally, as employees who work in the library customer-service environment, they have a unique role as teachers. “Often the people who do the work day-to-day make the best trainers” (Webb, as cited in Adams, 2009, p. 599).

Video Training

Due to its ubiquity, video lends itself as a premier training medium. “With nothing more than a smartphone or webcam, your subject matter experts can capture their knowledge in a fraction of time it would take to write and visually illustrate the information in a way that is not possible with text or static images” (Bixhorn, 2018, p. 54). Relevance to the digital native generation is an especially compelling motive for making use of current digital tools. “Technology promises to enhance our teaching methods as well as the reach that we can extend to prospective learners” (Salem & Peña, 2013, p. 178). In these case studies, the participants—Generation Z library assistants—have grown up with technology and therefore expect it in their environments. Additionally, 81.9% of employees worldwide believe videos are an effective training method (GP Strategies, 2018). Figure 2 demonstrates the importance of video as a learning tool.

Academic literature and trade publications have both emphasized the adoption of technology in academic libraries for many years. As Quinney, Smith, and Galbraith (2010) stress, “there is a great need for library staff and faculty to learn emerging technologies and to keep learning them as technology continues to change and advance” (p. 210).

Specifically, YouTube has seen an increase in usage from employees in the learning and development industry seeking to build their skills (Mimeo, 2018). Figure 3 demonstrates the growth in recent years.

There was a nine percent spike in YouTube use from 2017 to 2018, accounting for nearly half the employees surveyed. Encouraging library employees to develop their skills using YouTube would help them keep pace with current workplace trends.

Library Oscars at Two Libraries

As the academic library supports and fosters learning, I decided to apply these peer-teaching principles to library employees and use the medium of video. The experiment would allow librarians and staff supervisors to facilitate student-led teaching and learning. Students were assigned their topics based on their lack of mastery in order for them to better learn the material. The goal of the video initiative was two-fold: (1) to improve competencies and skill levels among current student employees, and (2) build a video library to utilize in the training of subsequent new hires.

I initiated the process at two universities in Florida. Lynn University (2018) is a private, liberal arts college in Boca Raton, Florida, with 2,700 FTE students. I had already created a 60-page handbook that included library policy and procedure, featuring visual aids and instructions. The library had eight full-time librarians, one academic editor, two part-time staff members, and 16-20 student employees. Stetson University is an independent, liberal arts college in DeLand, Florida, with 3,100 undergraduate students (Stetson, 2019). It has four colleges and schools located across Central Florida. The main campus’s duPont-Ball Library employs eight full-time librarians, one part-time librarian, two part-time and ten full-time staff, and 25-30 student employees.

At Lynn University, most student assistants worked in one location, the Information Desk. I divided the staff manual into smaller, manageable subjects that the students could use as material to create their videos. The students took these assignments and, due to their other curricular commitments and various obligations during the semester, were given two and a half months to create the videos. The Lynn University Library assignments included the following subjects:

- Confidentiality

- Interlibrary loan procedures for student workers (helping users with requests and circulation issues regarding the procedures to check ILLs in and out)

- Integrated library system procedures for checking items in and out

(with a focus on addressing common errors)

- Renewing items (notably the exceptions that occur with ILL, course and textbook reserve, equipment, etc.)

- Opening/closing procedures

- Daily tasks (e.g., checking the book drop/reshelving books/shelf reading/housekeeping)

- Printing procedures for different user groups (i.e., students, staff, and visitors)

- Customer service (greeting patrons, etc.) & telephone etiquette (methods for answering the phone, placing callers on hold, finding numbers for library staff/librarians, and transferring)

- Searching integrated library system for books, videos, etc.)

- Creating holds for patrons

- Circulation loan policy for various users

- Music library (introduction, loan rules, renewals, Lynn Conservatory, circulating items)

- Safety & emergency procedures

- Non-library services and departments located in the library building

- Shelf reading & course reserves

- Textbook reserves

I assigned subjects to students depending upon the length of time students worked at the library and their familiarity with the subjects. Because of the large number of student employees, collaborative work was permitted, particularly on closely-related subjects. With this first iteration of the Library Oscars, I employed a good dose of flexibility. Later, at Stetson, a few exceptional circumstances arose which prevented two students from creating videos. Instead, they were allowed an opportunity to create PowerPoint presentations, which could then be animated and converted to video using Camtasia.

The directions included the task and logistics. The employees received the criteria by which their videos would be judged: creativity, content, effectiveness of message, and overall enjoyment. The message included clear deadlines for submissions and the date of the Library Oscars event, as well as an incentive to submit their best work (a small financial award for the best video as chosen by their peers, librarians, and staff). Incentivizing the project gave the students a boost in motivation. This extrinsic motivation stimulated particularly creative work. “Rewards have a major impact on human behavior,” as Hytti, Stenholm, Heinonen, and Seikkula-Leino (2010) stated, and again emphasized that “rewarding learning experiences can change the direction of the person’s motivation” (p. 591). We made it clear that the students could ask for assistance, although they would ultimately be responsible for their project.

The process at Stetson University included several differences. In the spring and summer of 2019, I collaborated with the circulation supervisors, who had already created an employee handbook for library assistants and were in the process of updating the manual. The summer months brought a new crop of students, which made the timing ideal. However, there were only ten participating students compared to the sixteen at Lynn University, in large part due to the academic calendar. Choosing which student would get which subject was a critical piece of the process. After much deliberation and adjustment, the Stetson supervisors and I decided on subjects and informed the students of their assignments. With fewer patrons in the library, they had ample time to complete their projects in three weeks. Additionally, the circulation coordinator offered extra hours to students to work on their assignments outside of their regular shifts to finish. The Stetson student handbook had several subjects that were the same as Lynn Library’s, but it also included the following:

- Special shelving sections including YA/ picture books /juvenile fiction, periodicals/reference

- Equipment procedures (e.g., post-check-in procedures plus shelving locations)

- Missing shifts (e.g., how to address missing work, calling in/out, and covering shifts)

The Stetson group did not cover the music library, safety and emergency procedures, non-library services and departments located in library building, or textbook and course reserves.

During the period between assignment and submission at both libraries, students solicited help, including technical assistance with recording equipment and requesting that staff serve as “actors.” Supervisors encouraged students to check out audiovisual equipment in the library, including camcorders, cameras, microphones, laptops, etc. Students also solicited help with video editing software in the computer area. Both libraries featured the Adobe Creative Suite with Acrobat Premier Pro in addition to the built-in iMovie program on the Macs and licensed versions of Camtasia.

The video creation process also served as teaching and learning opportunities. In one example, from the endeavor at Stetson, a new student who had only worked for a few weeks did not wholly understand what reference books were. Fortunately, the student requested help before the submission deadline, which allowed time for additional training.

Another aspect of the Library Oscars involved adding an element of amusement to the videos. I produced commercials and messages to encourage employee creativity and the use of comic elements in their productions, which aligns with Poirier and Wilhelm’s (2014) contention that “humor creates a relaxed, engaging, and safe environment” for learning and teaching (p. 2). The brief commercial invited all available faculty and staff to support the initiative.

Over the course of both initiatives, it was imperative to address copyright compliance. The project instructions allowed for the use of copyrighted materials. The students were encouraged to find items and music under the Creative Commons licensing agreement. Still, due to the nature of the project, copyright-protected content was not prohibited.

While students prepared their videos, I created an unlisted YouTube channel that, due to the internal nature of the project, was not to be shared on social media platforms or with a broader audience beyond either library. Due to the large size of video files, staff created a unique folder on the library’s shared drive. Once submitted, I uploaded the files to the YouTube channel, and then distributed the complete playlist to library staff and student assistants before the event.

We asked everyone to watch the videos by themselves and then rate each one. At both Stetson and Lynn, this list included approximately 30 employees at each location. The student library assistants rated their peers’ videos based on their favorite three and were not allowed to vote for their own production. All students at both universities met the deadline for voting, set approximately one week before the “Oscars” event.

Voting details and Oscars event

To expedite the voting process at both institutions, I created a simple rubric addressing four criteria: creativity, content, effectiveness of the message, and enjoyment. Figure 4 demonstrates how staff, assistants, and librarians were encouraged to use the form to help decide their favorites. Employees were not required to use the rubric, but they were given the option. The rubric was helpful due to the high quality and variety of the submissions. Several employees mentioned the challenge in selecting the best. One librarian said, “I liked so many of them that I’m glad I needed the form.” “It was really hard to pick the top ones,” another employee noted. Another stated that “they all did such a nice job. It was difficult to choose!”

Over 75 percent of staff and librarians (and 100 percent of the student assistants) cast votes for videos. The viewing and voting process introduced employees to each other in an informal way, creating a bonding experience for the participants. From the 23 staff and librarians who voted at Stetson, 12 people returned their completed rubric score sheets with their votes. Several librarians made additional comments when submitting their choices. One said, “Enjoyed the videos—we have creative students!” Another said, “These are going to be fun to watch together.” Figure 4 is one of the forms a Stetson employee submitted:

For the student employees who created videos, the voting phase was vital because it required them to watch their peers’ productions—a significant element in the training exercise. The incentive for winning helped interest these students, as did their curiosity about what their peers created. As Berry (2008) noted, “peer pressure can act as a motivational force” (p. 152). This positive peer pressure helped the students; supervisors and librarians reported overhearing the students encouraging each other to work on and finish their projects.

The students voiced their reactions. “This was a fun project making and watching everyone else’s videos,” one student said. Another said, “The other videos were all entertaining, as well as informative.” After submitting her videos, the same employee said, “Thank you for this opportunity to create a video that was enjoyable during every second it took to make.” The act of watching the productions for the purpose of voting became an engaging learning tool, which researchers have confirmed is an effective way to teach. As Berry (2008) reported, the “active learning component added a positive influence on recall and learning” (p. 150). The learning was built-in to the entire process, from video creation through voting, to the culminating group function at the Library Oscars.

I encouraged all members of the organization to attend the live Library Oscars event, which they did at both Lynn and Stetson. The importance of creating a culminating event was a crucial step in the process. The incentive to have an “Oscars party” came with the requirement that all student workers view and rate the videos. Library assistants were the primary audience for the films, but broad inclusion was intended to foster coherence in the library, as well as understanding and empathy. The focus during and after clips remained on the positive aspects of the productions, including the information, storytelling, use of digital effects, acting or demonstrating, high-quality photography, etc. The initiative allowed employees to bond in a way that workday activities generally do not offer. The librarians’ attendance helped reinforce the significance of the student employees’ work and achievements.

I promoted the event as a celebration of creativity and achievement. In both cases, staff gathered in a classroom large enough to allow everyone to watch the videos. A colleague and I served as hosts for the event, guiding the audience through each video or at least a clip of each video, and then calling each student assistant to the front to receive an “Oscar” and applause for their work. At the end of the event, the group celebrated the top three videos and awarded gift card prizes to the winning students.

The overall initiative required an atmosphere where making mistakes was both necessary and productive. The Library Oscars project encouraged employees to take risks in learning. Whitten (2018) contends that “in the post-university world, failure is an inevitable consequence of trying to achieve things, being ambitious and taking risks; dealing with disappointment and building the resilience to learn from mistakes and persevere is a crucial life skill” (p. 3). In customer-focused library work, the need for a pliable learning environment was critical, mainly because library users needed help with various inquiries and frequently make mistakes themselves. Perhaps if the student employees were afforded the space to fail and learn from their errors, they would be more likely to demonstrate forbearance on library visitors.

Numerous studies have evidenced the need to create challenging assignments that meet student skill sets but do not exceed them. Schweinle and Helming (2011) posit that “optimal levels of challenge are not only necessary for learning and talent development, but also for student involvement, intrinsic motivation, and academic success” (p. 529-30). The fact that the assignment pushed the students and required them to concentrate and exert considerable effort, creativity, and problem-solving acumen, made the experience rewarding to them.

Similar to Schweinle and Helming’s 2011 study, the Library Oscars initiative demonstrated that successful student employees “reported higher efficacy, engagement, and intrinsic interest value” (p. 541). One of the prize winners at the Library Oscars event reported that “this was my favorite day at work ever.”

An additional appeal of the process was its low expense. The total cost of the Library Oscars was less than $150 at Stetson University and $200 at Lynn University. The supplies included refreshments and gift cards for the prize winners. “Appreciative feedback or praising an individual’s work is inexpensive and lets an employee know what he or she is doing well.” (Bradigan, & Hartel, 2013, p. 17).

Results and Implications

For the first initiative at Lynn University, the process was in its initial conception and therefore untested. The instructions and process were necessarily elastic. Issues included extending the time allowed to complete assignments and permitting videos to exceed the four-minute time limit—particularly those with combined subjects.

The second iteration improved at Stetson, although it presented other challenges—namely, that of enlisting the circulation supervisors. Since I did not directly supervise the students, the process depended on the supervisors’ established relationships with the assistants. At Stetson, there was a stronger emphasis on helping students overcome technical issues, explaining expectations, and encouraging students to take risks. The second round of this initiative benefited from the lessons learned from the first iteration.

After finishing the process at both libraries, the other supervisors and I shared the videos with newly hired employees to introduce policy, procedure, and culture of the library, creating a cyclical loop of content. The new hires reported how much they enjoyed watching the videos and getting to know their new coworkers.

After the Oscars, I found fewer mistakes were made in many areas addressed in the videos. For instance, one of the main issues at Lynn University concerned how to handle and manage the holds shelf. After a student created a video on the holds shelf procedures, there were fewer errors in the user records and on the shelf. Other librarians and staff members commented on the marked improvement in the student staff as well. At Stetson, librarians and staff mentioned the improvement of student skills as well as a more engaged group of workers. In fact, one unintended result of the process was the empathy and appreciation the librarians and full-time staff had for the student assistants. “They have to know a lot!” one librarian claimed, following with, “I’m glad they’re here.” Even those videos that did not receive many votes allowed the library staff to appreciate its entry-level members

Going forward at Stetson University, the supervisors and I agreed to conduct the initiative every other year in order to keep the content fresh and allow new employees an opportunity to create videos, as well as benefit from the reciprocal learning experience.

Conclusion

Academic libraries are uniquely positioned to create symbiotic, reciprocal work environments. The student employees offer librarians a unique perspective on arguably the most important, and certainly most populous, academic user group: the students. In turn, the employees’ understanding of how libraries work and why procedures exist enhances their experience at the library and allows them to benefit from the services and resources the library offers. As Melilli, Mitola, and Hunsaker (2016) relate, “meaningful work experiences can provide students with additional learning opportunities which can make up for time away from studying” (p. 431).

Training students serves “to increase productivity but also to motivate and inspire workers by letting them know how important their jobs are” (Ajie, 2019, p. 10). A successful library values its entry-level employees and seeks to make their experiences as rewarding as possible. The Library Oscars offered an opportunity to create an affirmatory experience for the staff and encouraged the idea of building a positive organizational culture.

The initiative provided the new generation of college students an interactive opportunity to learn. As Miller (2014) affirms, “in our networked world, students are eager for hands-on experiences” (p. 341). The Library Oscars at both universities provided opportunities for experiential learning. There were mistakes in the videos, and few would be ideal to use as promotional material—although, with a little editing, many of them would work at least in part. The goal was not to create masterful art but to improve mastery of a subject by learning it and then teaching it to peers.

References

Adams, C. (2009). Library staff development at the university of Auckland library – te tumu herenga: Endeavouring to “get what it takes” in an academic library. Library Management, 30(8), 593-607. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120911006557

Ajie, I. (2019, February). ICT training and development of 21st century. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1-17.

ATD. (2018, December 31). Share of organizations worldwide who use on-the-job training to a high extent in 2017, by type [Chart]. In Statista. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/958124/workplace-training-on-the-job-learning-types-used/

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (2016). Learning assessment techniques: A handbook for college faculty. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Berry, W. (2008). Surviving Lecture: A Pedagogical Alternative. College Teaching, 56(3), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.56.3.149-153

Bixhorn, A. (2018). Five ways to ensure your video content meets your training requirements. Strategic HR Review, 17(1), 53-54. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-10-2017-0071

Bradigan, P.S. & Hartel, L. J. (2013). Organizational culture and leadership: exploring perceptions relationships. In Blessinger, K., & Hrycaj, P. (Eds.), Workplace culture in academic libraries: The early 21st century. Oxford, UK: Chandos.

Cottrell, T. L., & Bell, B. (2015). Library savings through student labor. The Bottom Line, 28(3), 82-86. https//doi.org/10.1108/BL-05-2015-0006

Davis, E., & Lundstrom, K. (2011). Creating effective staff development committees: A case study. New Library World, 112(7), 334-346. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801111150468

De Rosa, C. & OCLC. (2006). College students’ perceptions of libraries and information resources: A report to the OCLC membership. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC Online Computer Library Center. Fitsimmons, G. (2012). The policy/procedure manual, part II. The Bottom Line, 25(1), 13-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/08880451211229162

GP Strategies. (May 15, 2018). Share of employees worldwide who believe learning technologies are effective in 2018, by type of technology [Chart]. In Statista. Retrieved July 23, 2019 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/885952/effectiveness-of-learning-technologies-worldwide-by-type/

Graybill, J. O., Hudson Carpenter, M. T., Offord, J.,Jr, Piorun, M., & Shaffer, G. (2013). Employee onboarding: Identification of best practices in ACRL libraries. Library Management, 34(3), 200-218. https:// doi.org /10.1108/01435121311310897

Hytti, U., Stenholm, P., Heinonen, J., & Seikkula-Leino, J. (2010). Perceived learning outcomes in entrepreneurship education: The impact of student motivation and team behaviour. Education & Training, 52(8), 587-606. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011088935

Klein, S. R. (2003). Peer Teaching: Learn by teaching “docendo discimus.” Journal of Teaching in Marriage and Family, 3(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1300/J226v03n02_04

Lynn University. (2018). 2017-2018 Common Data Set. Retrieved from https://www.lynn.edu/uploads/pdf/Lynn-University-College-Board-Common-Data-Set-2017-18.pdf

Maxey-Harris, C., Cross, J., & McFarland, T. (2010). Student workers: The untapped resource for library professions. Library Trends, 59(1), 147-165, 374, 377.

McCabe, J. (2015). Learning the brain in introductory psychology: Examining the generation effect for mnemonics and examples. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 203-210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315587617

Melilli, A., Mitola, R., & Hunsaker, A. (2016). Contributing to the library student employee experience: Perceptions of a student development program. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 430-437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.005

Miller, K. E. (2014). Imagine! on the future of teaching and learning and the academic research library. Portal : Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 329-351. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0018

Mimeo. (2018, May 3). What resources do you use to build your skills? [Chart]. In Statista. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/826199/skills-building-learning-and-development/

O’Neil, F., & Comley, J. (2010). Models and management of student employees in an Australian university library. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 41(2), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2010.10721448

Poirier, T. I., & Wilhelm, M. (2014). Use of humor to enhance learning: Bull’s eye or off the mark. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 78(2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe78227

Quinney, K. L., Smith, S. D., & Galbraith, Q. (2010). Bridging the gap: Self-directed staff technology training. Information Technology and Libraries, 29(4), 205-213.

Robinson, K. P., Runcie, R., Manassi, T. M., & Mckoy-Johnson, F. (2015). Establishing a competencies framework for a Caribbean academic library: The case of the UWI library, Mona campus. Library Management, 36(1), 23-39. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2014-0123

Salem, B., & Peña, C. (2013). Training with technology: How information technology enhanced the RDA training experience at the University of Pittsburgh. Pennsylvania Libraries, 1(2), 168-n/a. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2013.42

Schweinle, A., & Helming, L. M. (2011). Success and motivation among college students. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 14(4), 529-546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-011-9157-z

Stetson University. (2019). Just the facts brochure 2018-19. Retrieved from https://www.stetson.edu/administration/institutional-research/media/just-the-facts-2018-19.pdf

Whitton, N. (2018). Playful learning: Tools, techniques, and tactics. Research in Learning Technology, 26. http://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2035

Wow! Makes Libraries the happening place; combining teaching/learning with fun and rewards, while encouraging creative uniqueness!

Amazing educator, Hunter Murphy!

Excellent article & resource. I can’t wait until we are all on campus to give this a go. Thanks, Hunter!

“A student”?! I’m flattered :’)