Noah Lenstra

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7613-066X

University of North Carolina at Greensboro Department of Information, Library, & Research Sciences

njlenstr@uncg.edu

Christine D’Arpa

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8999-9479

Wayne State University School of Information Sciences

cdarpa2@wayne.edu

Abstract

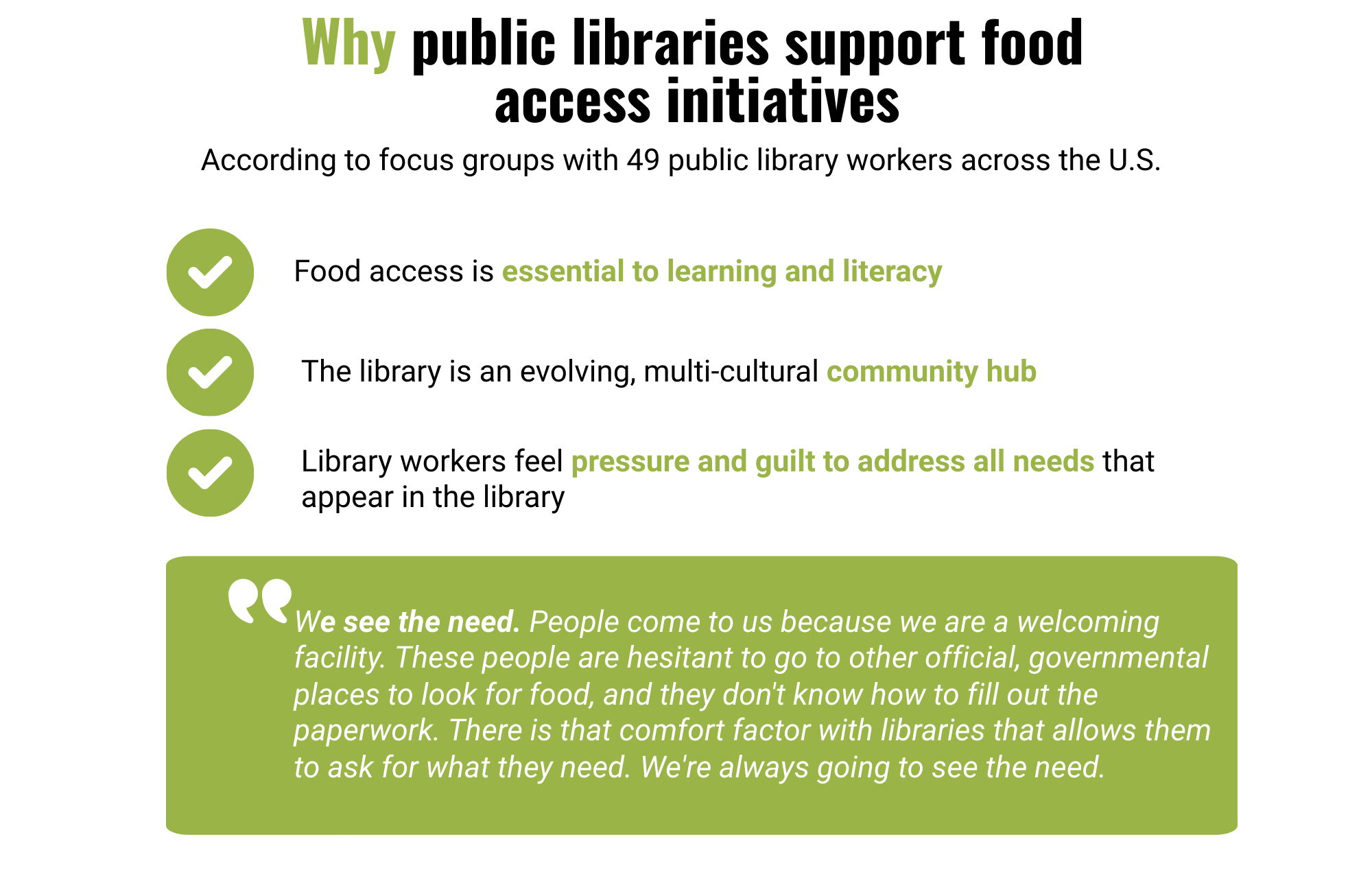

Food justice is a topic many working in public libraries wish to understand and put into action. Many struggle to do so in a way that is sustainable for their institutions and for library workers themselves. Based on focus groups with public library workers conducted from November 2023 to March 2024, we developed five themes that encompass how this changing role is conceptualized by library workers: (1) The library is an evolving, multi-cultural community resource and hub, (2) Food access is essential to learning and literacy, (3) Library workers feel pressure and guilt to address all needs and individuals, (4) Procedures and policies integrate food work into library work, and (5) Partnerships integrate library work into food work. A research agenda concludes with other additional work needed to understand not only this topic, but to more generally understand how public libraries work creatively with and alongside their communities to address evolving community needs.

Introduction

Public libraries and library workers transform how they engage and serve communities by developing creative partnerships with a broad range of community-based organizations and individuals (Holt, 1999). One domain of interest and concern during the last five years, and particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, has been food justice and more specifically hunger, limited access to food, and the critical need for a more equitable and just food system (Public Library Association, 2022). To understand how public library workers participate in community-based food justice initiatives, we organized a series of online focus groups to hear how this work is discussed and conceptualized. The results not only form a solid foundation from which to pursue further work on this topic but contribute to a better understanding of public libraries as community cornerstones and catalysts.

Literature Review

The topic of food and public librarianship is not a new one. For example, in 1978, the newsletter of the Social Responsibilities Roundtable of the American Library Association published “Nutrition: A Federal Food Primer.” Zang (1978) writes, “For the library – and the socially responsible librarian – there is a growing literature on the various [federal] food programs,” that needs to be understood. “Ignorance about available food resources means poor people have fewer choices about how to meet their food needs. We [librarians] should not contribute to that situation.”

Figure 1. Libraries partner to increase food literacy and build food justice in communities.

Figure 1. Libraries partner to increase food literacy and build food justice in communities.

However, it is only during the last fifteen years that sustained scholarship on how to most effectively connect food and librarianship has emerged, with especially strong attention during and after the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Peer reviewed research on this topic includes studies of public library-based nutrition education for youth (Porter, Liescheidt, & Dyuff, 1998; Freedman & Nickell, 2010; Concannon, Rafferty, & Swanson-Farmarco, 2011; Woodson, Timm, & Jones, 2011), summer meal programs (Rauseo & Edwards, 2013; Bruce et al., 2017; de la Cruz et al., 2020), community gardens (Jordan, 2013; D’Arpa, Lenstra & Rubenstein, 2020), and seed libraries (Tanner & Goodman, 2017; Peekhaus, 2018; Cohn, 2024). Studies have also considered more generally how public libraries work with community partners around food-related topics. These include studies of partnerships with the US Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education program (SNAP-Ed program) (Draper, 2021), agriculture-based community engagement (Singh, Mehra, & Sikes, 2022), and case studies of public library partnerships in particular places (Lenstra & Floyd, 2021). Many of these strategies were featured in the practitioner-oriented manual, “Food Literacy Programs, Resources, and Ideas for Libraries” (Dodge, 2020).

Based on this past scholarship, we concluded (Lenstra & D’Arpa, 2019) that across the United States, public library workers support food justice by collaborating with community partners to provide access to resources, information, and services. Examples of this work include connecting communities with food-related information and books, distributing fresh and packaged food, organizing cooking classes, establishing seed libraries, cultivating community gardens, and supporting farmers markets (Figure 1). This work is often done through partnerships with local Cooperative Extension educators,1 farmers, farmers markets, chefs, and gardeners.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought massive disruptions in food systems which significantly affected access to food. It also saw increasing interest among public libraries in how to respond with and alongside their communities to these disruptions. OCLC’s 2020 study of how library leaders grappled with pandemic-fueled changes to library operations found that libraries were increasingly collaborating with local agencies to address pandemic issues, such as by distributing food to those in need (Connaway, 2021). The Public Library Association included questions on food insecurity in its February 2021 survey of the field, finding that 28.3% of 2,967 public library workers either were currently partnering or saw an opportunity to partner with others on food insecurity issues (PLA, 2022). Furthermore, 39.8% were interested in developing better competencies for how libraries work “with vulnerable populations (such as those experiencing food insecurity, homelessness, addiction).” (ibid.)

These findings led national organizations such as the Urban Libraries Council (2023) and the American Library Association (2024) to highlight how public libraries and their partners work together to address food issues in their communities. Less well understood in this national literature is the fact that public library workers themselves struggle with food insecurity. This was especially apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic disruption of food access and systems. Coverage of food insecurity within the public library workforce has instead emerged through local media sources.2

Despite this scholarly attention to food security, food partnerships, and public librarianship, what remains to be understood is how the work gets done. That is, from the perspective of public library workers, what does this work — food work — involve in terms of time, resources, and support? How are decisions to engage in food work by public libraries made and assessed? How do public library workers build support for food justice in ways that make this work visible, effective, funded, supported, and sustainable? These questions remain largely unasked, and therefore unanswered. We argue that this knowledge is necessary to more strategically support the intersections of food justice and public library work.

Theoretical Framing: Food Justice

In a 2018 interview by The Guardian newspaper, activist and farmer Karen Washington noted that the phrase food desert is an “outsider term” not used by people in communities. Instead, she argued, we should use food apartheid because it “looks at the whole food system, along with race, geography, faith, and economics” (Brones, 2018). Food justice work is grounded in the analysis offered by Washington. It directly addresses those inequities with its focus on the right to fresh, healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food (Sevilla, 2021.) Many food justice advocates and activists expand the definition to include access to locally grown foods, and community influence on and participation in food systems. And others value the broad range of workers in our food systems and advocate for a living wage with benefits and policies that protect them. Food justice work strives toward a society that is more just, fair, and democratic and is itself an aspect of social and economic justice. Food justice work brings a diverse array of activists and advocates to the table (Murray et al, 2023).

Methods

The project team consisted of faculty and graduate students from Library and Information Science programs at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Wayne State University in Detroit. That team worked with a strategically selected group of research fellows (library workers, community and food justice activists, and scholars) to structure and convene five, one-hour, recorded online conversations to discuss and learn how and why public libraries become involved in food justice efforts (Lenstra, D’Arpa, Thornburg, Williams, 2024). This research was approved by the University of North Carolina at Greensboro Office of Research Integrity and its Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The focus groups were structured around open-ended questions we developed to understand why, how, and with whom do public library workers engage food justice issues. We also asked participants what they wanted both other library workers and the public to know about this topic. During focus groups, library workers shared with us, and with each other, the unique paths that led them to think about and work toward food justice.

As the data was collected, the research team closely coded and analyzed the focus group transcripts, as well as surveys completed by focus group participants. Thematic analysis was the technique used for analysis: Researchers applying this technique closely analyze texts to discern themes and patterns (Terry et al., 2017). Preliminary findings and drafts were shared with research fellows to solicit feedback. The results emerged from an intensive and iterative process of collaborative coding and sensemaking driven by the core research team in partnership with the research fellows. Together we discussed and made sense of what we heard in the focus group conversations.

Limitations. As an exploratory study, this project did not set out to definitively describe all intersections of public library work and food justice. Instead, its aim was to surface key topics and themes identified by library workers themselves. In addition to limitations that emerge from the self-selecting nature of this sample, to fully understand this topic, we need to listen not only to library workers, but also to their community partners, and other members of their community. A larger study that was more strategically designed to fill some of these gaps could help build a more comprehensive understanding of how public library work and food justice come together.

Results

Description of sample

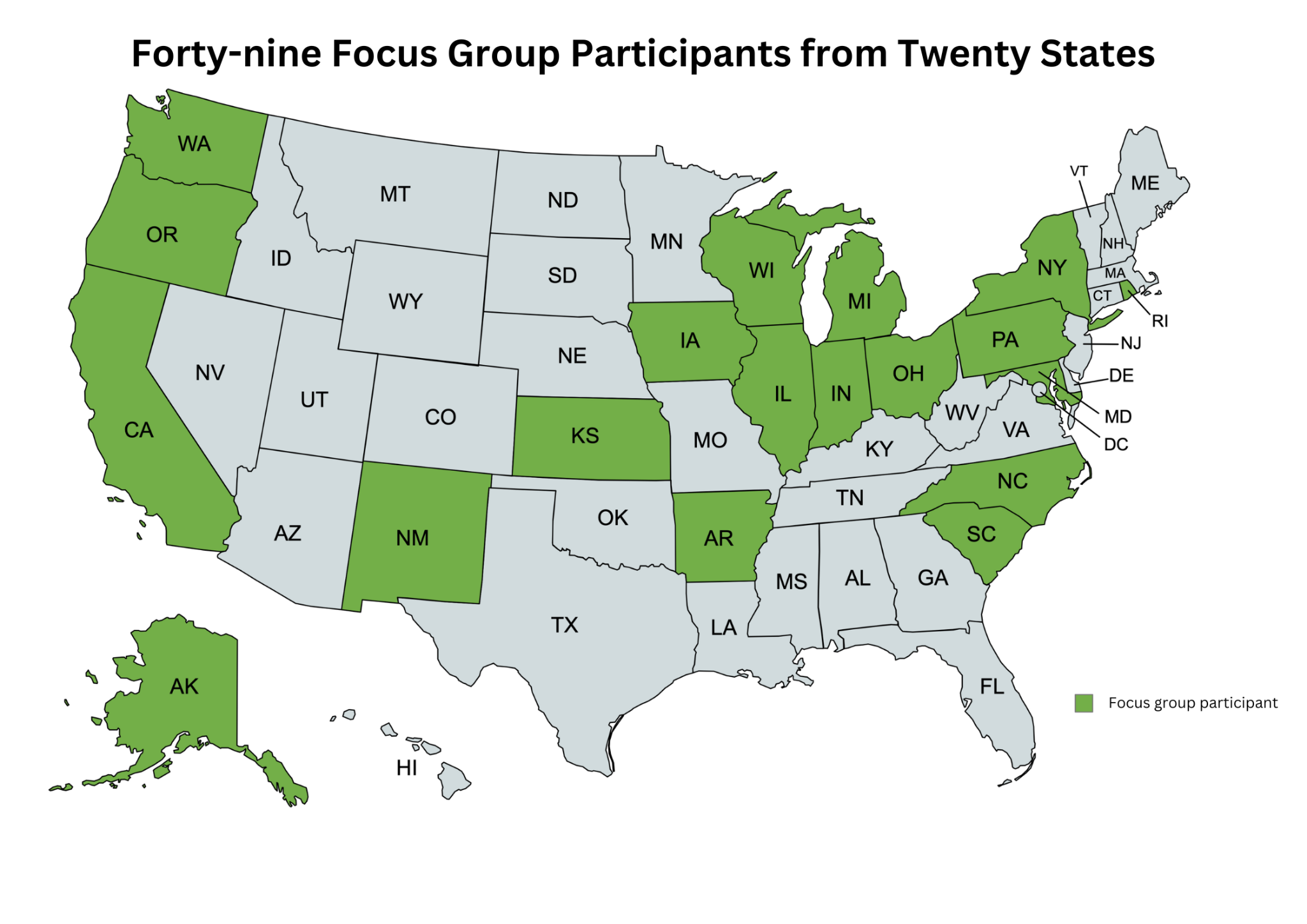

The call for participation in Fall 2023 elicited 148 expressions of interest from public library workers and students in 31 U.S. states and territories (Figure 2). Based on the complexities of scheduling and other factors, in the end we hosted five focus groups, engaging 49 individuals from 20 states. The first focus group in November 2024 had nine participants, the second and third focus groups in December 2024 had 12 and 13 participants, respectively. The fourth focus group in January 2025 had six participants. The final focus group in early March 2025 had nine participants.

Most focus group participants had prior experiences related to promoting food justice, food security, food access, farming/gardening, or several other related areas. The states where the research teams are based (North Carolina and Michigan) were over-represented together encompassing 35% of all focus group participants.

Figure 2. Map of states where focus group participants were located

Figure 2. Map of states where focus group participants were located

In a pre-focus group survey, most participants (86%) reported they currently work in a public library. Those that said they did not were all students in LIS master’s programs, most of whom reported past paid and/or volunteer positions in public libraries. Rural, suburban, and urban communities were equally represented among participants, with nearly 40% each saying their libraries served these types of communities; participants were asked to select all that apply, and most said their libraries served multiple types of communities.

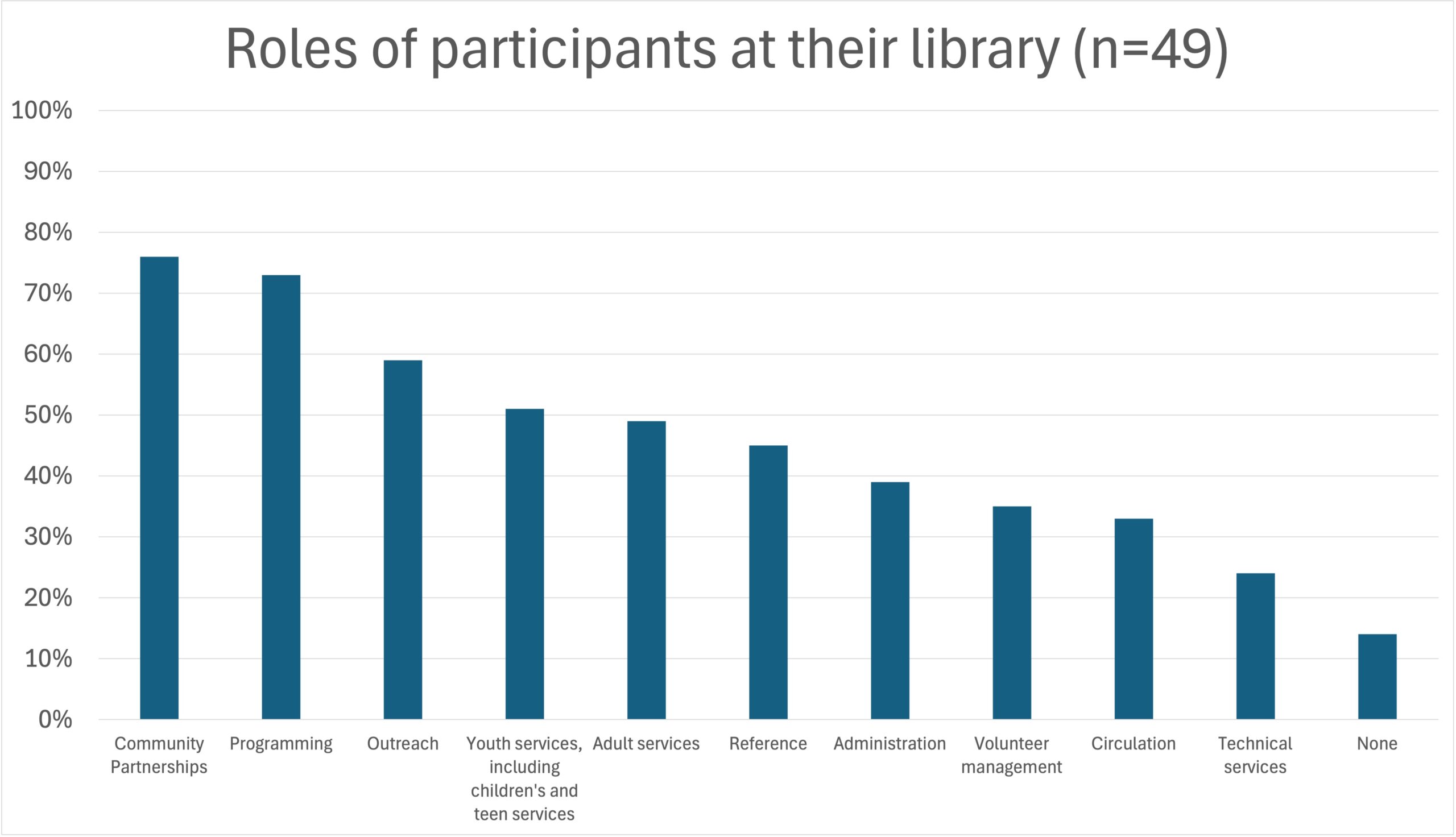

We asked participants to select what duties they had at their library, and they were invited to select more than one option. More than half of participants reported their roles at the library involved community partnerships, programming, outreach, and youth services (Figure 3). Less than half said their jobs included adult services, reference, administration, volunteer management, circulation, or technical services.

Figure 3: Focus group participants’ roles

Figure 3: Focus group participants’ roles

How public library workers talked about food work

Analysis of focus group transcripts revealed five themes. Three focus on why public library workers engage in this work, and two focus on how the work is carried out (Figure 4).

- The library is an evolving, multi-cultural community hub

- Food access is essential to learning and literacy

- Library workers feel pressure and guilt to serve all community needs

- Policies and procedures integrate food work into library work

- Partnerships integrate library work into food work

Figure 4. Reasons public librarians support food initiatives.

Motivations to do the work

1. The library is an evolving, multi-cultural community resource

Throughout focus group interviews library workers discussed the idea that the public library is the place where people go in their community; it is a place that changes over time, and a place that serves all members of the community. Within this theme we heard discussion of related topics including (1) concern about barriers that inhibit access to the library for some patrons and (2) the importance of an environment like the library where people can go and access food and other resources without bureaucratic requirements like filling out forms or judgment such as being made to feel like one must identify as being “poor” to utilize resources.

The following statement by one of the focus group participants serves to illustrate this theme:

We have 27 branches and in every single location, the library is where community things happen. We really are the community connection. We’re where you go, and we are here to meet community needs, so if one of them is food justice then of course it’s going be us.

The idea of public libraries evolving or changing over time is the foundation of understanding of the library as a community hub. As community needs change

so too does the library; as community demographics change so too does the library.

2. Food access is essential to learning and literacy

A common concern in conversations on food security and public libraries is the idea that if children can’t access food, learning and literacy are impossible. For instance, the national Collaborative Summer Library Program (2019) has maintained a Libraries and Summer Food guide for public libraries. That guide opens with the statement, “Hungry kids don’t read.” This sentiment also surfaced in our focus groups. We heard that library workers think about the critical importance of food access not only for youth but also for adults, and even for library workers themselves. We heard that in rural libraries salaries do not keep up with inflation so that too often even library directors qualify for food assistance programs and may need supplemental access to food. Others discussed how they felt like they had to work to address the primary need for food and nourishment for all ages before they could offer enrichment services for their patrons. As one participant said, “we kind of took the approach of you can’t engage or enrich or learn if you’re hungry.”

3. Libraries workers experience pressure and guilt to meet all needs

Related to the idea that food access is essential to learning and literacy is the idea that public library workers experience tremendous pressure and often guilt if they see needs that they cannot meet. As one participant said:

If you don’t have the staff for it, you will feel guilty that you didn’t do it, and there can be a lot of guilt related to seeing this need. But I can’t [meet the need] because I don’t have the people for it, I don’t have the resources.

How does the work function in public libraries?

Two partial solutions to addressing and mitigating these pressures that emerged in the focus groups were to institutionalize and to extend — institutionalize through policies and procedures that shift the responsibility from the individual library worker to the library itself, and extend through partnerships that share the work across individuals, organizations, and communities.

4. Policies and procedures integrate food work into library work

Public library workers pointed to policy development and training that was needed help ensure this work is fairly distributed across the organization. Participants discussed challenges they navigated while working to institutionalize this work. These included including the newness of food justice work, a lack of administrative or staff buy-in, and staff turnover. Participants pointed to solutions and challenges that need to be addressed to get to solutions.

One library worker said they felt like they had to start a food give-away program under-the-counter” because of resistance to this work by local elected officials:

[I]t was just too nontraditional for the mayor to deal with. He said it was not the role of the library to do that, and I told him we were open more hours than anything else in town because at that point we were open 66 hours a week. At that point, he just wouldn’t go with it. He moved it to the senior center where a group was supposed to be managing it, and within two months of them taking it over, they shut their whole program down. The food disappeared; we don’t know what happened to it. So, we sort of started [again] from scratch under-the-counter and we haven’t given up on it and we have a new mayor coming in.

There was general agreement among participants that changing policies and procedures takes time. One shared that the internal advocacy to transform her library system took more than a decade. She reported that the work to create institutional change did finally start to produce results:

Starting in 2024, [library administrators] will take into account [the amount of time needed to develop food programs] when they figure out the amount of staffing needed so that branches that have a greater amount of [food] programming will be staffed appropriately. It’s a lot of little teeny steps.

Discussions of institutionalizing this work overlap with discussions of what both future and current public library workers need to learn about this topic. One participant in the focus groups said:

[W]e had kids show up who had aged out of the foster system, and they were hungry, and they didn’t know what was out there for them. They were actually sleeping in the back of the library when I came in one day. I think this really needs to be discussed in library school. I mean, I know we can’t cover everything. We will not talk about the perfect mouse trap and how to expose them if they’re in the heater system, but I think this is an important enough topic that more of us need to be discussing it as a [library] profession. (emphasis added)

Another participant was even more direct, asking “How are we preparing public librarians for the actual job that they’re walking into?”

5. Partnerships integrate library work into food work

Several participants noted that for this topic to be sustainably integrated into public library work, partnerships are necessary and foundational. One said:

What I want people to know is we’re happy to be part of the solution. Bring us in. We need partners. We’re happy to be part of this. Don’t ask us to be the whole solution, but also don’t forget that we’re here.

Another said:“We’re always going to see the need. We don’t have to be the ones doing the work though.” A third said that they see their role as elevating the work others are doing: “we [found that we] can increase impact for other initiatives going on.” This requires, as a fourth participant pointed out, “just trying to put together resources so that we’re working together [and] finding other people who have information” and resources.

Throughout focus group interviews participants talked about the critical importance of doing this work in collaboration, alignment, and partnership with other individuals, organizations, and initiatives. For example, a participant said that in her community it has been important to

see this as something that can often be done through many partnerships that already exist in our communities and having the library as a place for those partnerships to convene.

We also heard the idea that partnerships were not without challenges. One interesting and common challenge we heard from public library workers was that they worried the time needed to cultivate effective partnerships could take them away from the work to meet critical and immediate food-related needs among their patrons. Participants also highlighted the communication work that goes into partnership building. One said:

We have all these different partners that are all doing food distribution, food, justice, but nobody’s talking to each other. Trying to work together, instead of having 2 or 3 different organizations doing the same thing: Together we’d be stronger. That’s really difficult, getting everybody working together.

Communication with municipal and county government officials also emerged as a type of partnership work public libraries are engaged in:

For me it’s also communication with my municipality. How do you make it seem [to local government] less odd that your library, which is essentially your only community center in the area, is providing food resources. And that’s been one of my bigger challenges.

The work involved in communicating that the library was part of the community ecosystem that supports food justice is part of the labor that goes into integrating food justice into public library work.

Discussion

Across the five focus groups, we heard library workers describe the intersections of food justice and public library work in five overlapping ways discussed in the previous section. Three describe why library workers are motivated to do this work and two describe how library workers do this labor.

We conclude by considering the implications of these findings in relation to: Perceptions of food work, what it means for public libraries to intervene in food systems, and funding and advocacy.

Perceptions. We need to better understand how public library workers come to think of themselves as workers engaged in supporting food justice. We found when we broached this topic during our first focus group that a focus group is not an ideal format for that type of reflection. An interview-based study would be much better at creating space for individual library workers to reflect on and unpack the personal and professional journeys that led to their personal interest in their work.

We also need to explore how public library workers would like the public to understand the intersections of food justice and public library work. This was touched on in focus groups when we heard that library workers want others to see them as partners and as people who see the needs, have access to resources and information, and who see themselves as committed to being part of solutions. In addition to developing and testing messaging campaigns to library peers and the public through diverse channels and formats, we also need to support library educators who also, according to our focus groups, need to do a better job of preparing LIS students for the realities of public library work, including the need for advocacy for this work.

The focus groups illustrated how food justice work overlaps with other social service partnerships library workers engage in. For instance, public library workers discussed food justice alongside other services like making hygiene and health products free at the library or partnering to address critical community issues like the housing crisis and the dearth of services and resources for the unhoused. The triple intersection of social services — food justice — public librarianship needs our attention as we work to understand challenges, opportunities, and long-term solutions.

Finally, we need more research to demonstrate the impact of food work by public libraries. The California State Library’s Lunch at the Library (2023) has kept detailed records on the impact of public library participation in USDA Summer Feeding Programs, but outside this initiative we know very little about the impacts of public library support for food justice. Much more work needs to be done to discover and evaluate impact. Both qualitative and quantitative data, including oral histories with library workers, can enrich our understanding and firmly root it in community stories about what can happen when public library workers collaborate with others to make a difference in their communities.

Intervening in food systems. A critical knowledge gap we have identified is the limited understanding of how public library workers transition from the identification of a need to the creation of — or entrance into — collaborative systems that address that need with an eye to, in this case, creating a just food system that values people over profit (Reich, 2024). Since this is a relatively new topic in many public libraries, discussions tend to focus on programming rather than on policies. In other words, the question library workers often ask is “What can we do now?” without also asking “What may we be able to do for the long-term?” and “What do we need in place to sustain the work?”

Relatedly, we only scratched the surface in terms of understanding how public library workers connect to or collaborate with partners such as educational institutions or nonprofits that are working to catalyze and amplify efforts to transform food systems through research, education, investing in communities, building public awareness, and advocacy. We see it as vitally important to understand how the trust the public places in libraries and library workers could translate to amplifying food justice work being done by researchers, non-profits, artists, and advocates.

Funding and Advocacy. During the past ten years, a novel approach to public library advocacy has emerged. People like sociologist Eric Klinenberg (2018) and political scientist Daniel Aldrich (2023) call for advocating for public libraries as part of our social infrastructure, funded with public monies alongside parks and other enriching public spaces to, among other things, support the trust and connectivity that help us as a society build collaborative and adaptive responses to major challenges. We argue that we need to get better at advocating for public libraries as part of the community-based social infrastructure that could begin to address the many ways and unjust food system and food apartheid impact individuals and communities and through that work move us toward food justice.

Some questions to consider include: If we think of public libraries as a type of social infrastructure funded to support the public good, what responsibilities does society have to ensure the library workforce is set up for success to work collaboratively with other institutions that are part of social infrastructure? At a local level, what does the institution of the public library need to do to support its employees so they can work with communities to find solutions to issues such as barriers to food access and hunger? As we heard from our focus group participants and as we have seen in media reporting (see literature review), public library workers themselves can experience food insecurity because so many are poorly compensated for their work. How can we ensure that library work is valued, and library workers fairly compensated with a living wage and other benefits, so they do not become the very population they work to assist? How do we increase community support and investment in local public libraries and library workers in ways that respect their expertise and autonomy? More generally, how does advocating for food justice overlap with advocating for public libraries, social infrastructure, and the public good?

Conclusions

From November 2023 to March 2024, a team of researchers engaged 49 public library workers and students in a series of focus group interviews designed to better understand the intersections of public library work and food justice. This research found that many public library workers feel a great deal of pressure in their jobs. This was best expressed as an expectation that they be “all things to all people.” Library workers knew the value of collaborative approaches but too often felt constrained by the urgency of the need and the limitations of time.

These findings have implications for how we support creative practices in public libraries through research, teaching, advocacy, and professional development. Rather than only present public libraries with blueprints for programs they could offer (e.g., a seed library or a Little Food Pantry), a more sustainable and strategic approach would be to invest in the institution, ensure it has secure and sufficient resources to fulfill its mission. That approach would also nurture and support skills-building in ways that help public libraries think and work creatively with others in their communities to support food justice. Part of this work includes developing tools and resources that will help public library workers and administrators frame food justice in terms of the enduring values of library work: social justice, equity of access, and community-engaged and community-led services.

The work public libraries and library workers do in communities requires renewed commitment to the idea of a public good. That commitment informs a common understanding of the unique role and a full appreciation of the values that guide the work of public libraries with and alongside communities.

Notes

1 The Cooperative Extension system was created via the US Smith-Lever Act of 1914. It funds and empowers land-grant universities to support agricultural and community development across the states they serve.

References

Aldrich, D. P. (2023). How libraries (and other social infrastructure spaces) will save us: The critical role of social infrastructure in democratic resilience. SSRN 4639061. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4639061

American Library Association (2024). State of America’s Libraries 2024. https://www.ala.org/news/state-americas-libraries-report-2024

Brones, A. (2018, May 15). Food apartheid: the root of the problem with America’s groceries, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/15/food-apartheid-food-deserts-racism-inequality-america-karen-washington-interview

Bruce, J. S., De La Cruz, M. M., Moreno, G., & Chamberlain, L. J. (2017). Lunch at the library: examination of a community-based approach to addressing summer food insecurity. Public Health Nutrition, 20(9), 1640-1649.

California State Library. (2023). Lunch at the Library Summer 2023 Report to the Legislature: 2022-2023 Fiscal Year. https://www.library.ca.gov/uploads/2024/02/LATL-Legislature-Report-Summer-2023.pdf

Collaborative Summer Library Program (CSLP). (2019). Libraries and Summer Food. https://www.cslpreads.org/libraries-and-summer-food/

Cohn, S. B. (2024). Lending seeds, growing justice: Seed lending in public and academic libraries. The Library Quarterly, 94(2), 117-133.

Concannon, M., Rafferty, E., & Swanson-Farmarco, C. (2011). Snacks in the stacks: Teaching youth nutrition in a public library. Journal of Extension, 49(5), n5.

Connaway, L.S., et al. (2021). New Model Library: Pandemic Effects and Library Directions. Dublin, OH: OCLC Research. https://doi.org/10.25333/2d1r-f907.

D’Arpa, C., Lenstra, N., & Rubenstein, E. (2020). Growing food at and through the local library: An exploratory study of an emerging role. In Roles and Responsibilities of Libraries in Increasing Consumer Health Literacy and Reducing Health Disparities (Vol. 47, pp. 41-59).

De La Cruz, M. M., Phan, K., & Bruce, J. S. (2020). More to offer than books: Stakeholder perceptions of a public library-based meal programme. Public Health Nutrition, 23(12), 2179-2188.

Dodge, H. (2020). Gather ‘Round the Table: Food Literacy Programs, Resources, and Ideas for Libraries. ALA Editions.

Draper, C. L. (2021). Exploring the feasibility of partnerships between public libraries and the SNAP-Ed program. Public Library Quarterly, 1-17.

Freedman, M. R., & Nickell, A. (2010). Impact of after-school nutrition workshops in a public library setting. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42(3), 192-196.

Holt, G. (1999). Public library partnerships: Mission-driven tools for 21st century success. LASIE: Library Automated Systems Information Exchange, 30(4), 36-67.

Jordan, M. W. (2013). Public library gardens: Playing a role in ecologically sustainable communities. In M. Dudley (Ed.), Public Libraries and Resilient Cities (pp. 101-110). ALA Editions.

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. Crown.

Lenstra, N., & D’Arpa, C. (2019). Food justice in the public library. The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion, 3(4), 45-67.

Lenstra, N., D’Arpa, C., Thornburg, E., & Williams, C. (2024, December 3). Public Librarianship & food justice: Exploring the intersections. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg//listing.aspx?id=48010

Lenstra, N., & Floyd, R. (2021). Wilkes county public library’s involvement in the food justice movements in rural North Carolina. In Social Justice Design and Implementation in Library and Information Science (pp. 62-72). Routledge.

Murray, S., Gale, F., Adams, D., & Dalton, L. (2023). A scoping review of the conceptualisations of food justice. Public Health Nutrition, 26(4), 725-737.

Peekhaus, W. (2018). Seed libraries: Sowing the seeds for community and public library resilience. The Library Quarterly, 88(3), 271-285.

Porter, D. T., Liescheidt, T., & Dyuff, R. L. (1998). Partnering with public libraries: Interactive nutrition education via Book Box. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 98(9), A47.

Public Library Association (2022). Survey of the Public Library Field. https://www.ala.org/pla/data/fieldsurvey

Rauseo, M. S. & Edwards, J. B. (2013). Summer foods, libraries, and resiliency: Creative problem solving and community partnerships in Massachusetts. In M. Dudley (Ed.), Public Libraries and Resilient Cities (pp. 89-100). ALA Editions.

Reich, R. (2024). Why giant mergers harm workers. https://robertreich.substack.com/p/the-biggest-grocery-merger-in-history

Sevilla, N. (2021). Food apartheid: Racialized access to healthy affordable food. Natural Resources Defense Council blog. https://www.nrdc.org/bio/nina-sevilla/food-apartheid-racialized-access-healthy-affordable-food.

Singh, V., Mehra, B., & Sikes, E. S. (2022). Agriculture-based community engagement in rural libraries. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 54(3), 404-414.

Tanner, R., & Goodman, B. (2017). Seed libraries: Lend a seed, grow a community. In Audio Recorders to Zucchini Seeds: Building a Library of Things. (2017). ABC-CLIO, 61-80.

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(17-37), 25-37.

Urban Libraries Council. (2023). Libraries and Food Security. https://www.urbanlibraries.org/files/ULC-White-Paper_Food-is-a-Right_2023.pdf

Woodson, D. E., Timm, D. F., & Jones, D. (2011). Teaching kids about healthy lifestyles through stories and games: Partnering with public libraries to reach local children. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 11(1), 59-69.

Zang, B. (March 1978). Nutrition: A federal food program primer. SRRT-ALA Newsletter #48, p. 3. https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/rt/content/SRRT/Newsletters/srrt048.pdf

Acknowledgements

Graduate Research Assistants Chloe Williams and Elizabeth Thornburg were instrumental in all stages of this endeavor. Thank you to Shaina Reese for assisting with final editing, to Lilly Fink Shapiro for work on visualizations, to Patricia Hswe and her team in the Public Knowledge program at Mellon for supporting this endeavor (Grant Number 20451390), and to the many staff members at Wayne State University and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for supporting the administrative aspects of this project.