by Amos Blanton, MA EdS.

Aarhus University

Abstract

This describes a case study of efforts to create the conditions for library educators to engage in a dialog between theory and practice intended to enable them to eventually develop a pedagogy of creativity and hands-on learning for the library. Over 14 months of biweekly meetings, 5 librarian educators led by the author studied constructionist learning theory and a method of doing practice based research from the pedagogy known as the Reggio Emilia approach, and ran two hands-on workshops for adults and children. Documentation from those workshops is included as well as an analysis of the challenges that became evident during the process. Implications for libraries as non-formal learning institutions are discussed.

Introduction

In A new model for the public library in the knowledge and experience society, Jochumsen et al. (2012) articulate a need for libraries to support learning as “a dialogue-oriented process that bases itself on the user’s own experiences and their wish to define their own learning needs.” This kind of learning “takes place in an informal environment – it happens through play, artistic activities and many other activities.” Towards this end, they describe a need to “translate the model’s more abstract concepts into a concrete reality.”

What Jochumsen et al. describe is not so much a set of discrete goals as it is a culture shift in the way libraries think about learning and how they serve their communities. Rather than facilitating the consumption of facts, they suggest that libraries could become a place where new ideas are created, playfully and in community. Many other libraries have been exploring a similar set of values about learning (Rasmussen, 2016), often involving giving citizens access to new creative technologies through makerspaces (Willingham & DeBoer, 2015; Einarsson & Hertzum, 2020). In terms of learning, this amounts to a tectonic shift – especially for the people working in the library. Instead of “shushing” to keep things quiet, this vision has them learning to elicit the citizen’s creativity and self-expression through a collection of skills that are the opposite of “shushing.”

Aarhus Public Libraries, co-sponsor of this research, have been working on developing “a library for people and not books” (Østergård, 2019) since their flagship library, Dokk1, was conceived a decade ago. Inspired by human-centered design, their vision states that “The library of the future should be co-created with the citizens” (Bech-Petersen, 2016). This is done through an ongoing dialog between the librarians and citizens, the principles of which are described in Design Thinking for Libraries: A Toolkit for Patron Centered Design (IDEO, 2015), which they co-authored with the design firm IDEO and Chicago Public Libraries.

This work describes investigations into the question of how to develop and facilitate hands-on playful and creative learning activities in the library, a subset of the broader challenge described by Jochumsen et al. 2012. The research question is: How can we create the conditions for a dialog between theory and practice that could enable library educators to develop a pedagogy of creativity and learning for the library? The goal here is to experiment with reflective processes that could create the conditions for practitioner educators working in libraries to ask and answer their own questions. These processes, as well as observations and challenges that emerged along the way, are described below.

One risk inherent to all project-driven organizations is that each project tends to generate ideas and insights that are tailored to its own needs. If there are many projects running concurrently, they can easily crowd out the space and time for reflection necessary for educators to convert specific insights into generalizable theory. I argue that what is required to meet Jochumsen et al.’s challenge in the long the run is a robust general theory of play and creativity in the library – a pedagogy. The goal of this research is to experiment with theory and methods for supporting reflective practice that could create the conditions for developing and refining such a pedagogy. These are drawn primarily from two traditions in progressive education: constructionism (Papert, 1980) and the Reggio Emilia approach (Guidici et al., 2008 and Krechevsky, et al. 2013).

As Dubin (1976) described it, “A theory tries to make sense out of the observable world by ordering the relationships among elements that constitute the theorist’s focus of attention in the real world” (in Weick, 1989). A pedagogy is a theory of learning that clarifies what kind of learning is valuable and why, and how best to create the conditions for it to occur (‘Pedagogy’, 2022). Like any theory that is useful for practitioners, it must enable them to make sense of what they observe, guide their interventions, and help them articulate why they do what they do for the stakeholders around them. In addition, it should provide a shared language with which to communicate with other library educators, and to collectively ask and answer subtle questions that enable the continuing evolution of the pedagogy.

Many librarians have little if any coursework addressing learning theories of any kind, as these are rarely offered as part of library science education programs (Montgomery, 2015, p.19). Educators working with learners in library makerspaces sometimes lack a coherent pedagogical strategy for supporting learners at different skill levels (Einarsson & Hertzum, 2020). Most existing pedagogy is strongly tied to formal learning environments like school, where learning tends to be compulsory and planned around a predetermined set of standards and goals. As contexts for learning, libraries share more similarities with other non-formal learning institutions like science centers and museums than they do with schools (Rogers, 2014). Non-formal learning institutions receive learners of all ages, often in family groups, and must try to engage them in ways that they find relevant and meaningful, or they won’t come back.

In exploring what sort of actions and structure could support the development of a pedagogy of creativity and learning in the library, my colleagues and I used a “try it and see” approach, utilizing inductive (Eisenhardt et al., 2016) and abductive reasoning, with the goal that theory would emerge from the practice through collective exploration and reflection. Over the course of 14 months I met biweekly online or in-person with 5 experienced library educators[1] in what was called the Creative Learning Research Group (hereafter referred to as the CLRG). Each educator brought a variety of skills and knowledge including experience design, the facilitation of creativity through crafting with small children, and the use of complex digital fabrication tools. All had experience with Design Thinking for Libraries (IDEO, 2015).

In the course of those meetings, we explored content (in the form of readings about various learning theories) and processes (in the form of reflective discussions) which had the potential to be useful and relevant in the context of the library. On two occasions we facilitated open-ended playful learning experiences together, and would have done many more were it not for the Covid-19 pandemic. We collected Documentation to use as evidence in our theoretical discussions, adapting methods that emerged out of the work of the children and educators of the city of Reggio Emilia, Italy (Guidici et al., 2008 and Krechevsky, et al. 2013) known as the Reggio Emilia approach. Our Documentation took the form of notes, quotes, observations and photographs of learners in the process of being creative, curated summaries of which are included in the findings section. This Documentation served as the evidence on which our theoretical interpretations were based.

In the analysis section, I suggest that library educators already use a patchwork of elements from various learning theories, but they rarely have space and time to reflect on or attempt to synthesize them. The practice of reflective Documentation shows potential as a means for generating new theoretical questions, ideas, and answers – the building blocks of a pedagogy. The lack of a clear articulation of what quality in creative learning activities in the library looks like is a challenge, one that may be made more difficult by epistemic issues associated with the division between academic research and practice.

In the Discussion section I describe a strategy for positioning learning in the library in relationship to learning in schools.

This work accepts as axiomatic the following ideas which, while debatable, are beyond the scope of this work to defend: 1) Each learner’s experience is idiosyncratic, a process of integration that is contingent on their own pre-existing knowledge, skills, and interests as well as the values of their surrounding culture. And 2) in order to be useful and effective, theories of learning must be reinterpreted critically by educators for use in their own cultural and physical context (Guidici et al., 2008). Librarian educators can of course take inspiration from a variety of learning theories. But in order to be successful along the lines that Jochumsen et al. describe, they must ultimately craft their own, tailored to their own local context. This research describes a small step down that path. In the longer term, success is not so much a specific outcome as it is an effective process through which librarian educators can continually develop and refine their approach to supporting learning and creativity within the local cultures that surround them.

Background

This research is part of my PhD research, titled Experimenting, Experiencing Reflecting: Collective Creativity in the Library, and is funded by Aarhus Public Libraries and the Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting Research Project (EER). EER is a science and art based research collaboration between the Interacting Minds Centre at Aarhus University and Studio Olafur Eliasson, which itself is funded by the Carlsberg Foundation. The goal of my PhD research is to explore collective creativity through the design of materials, activities, facilitation strategies, and environments that support it. The work described here was part of the process of laying a foundation for design-based research into collective creativity in the library.

Prior to beginning this PhD research, I worked as a designer of activities, environments, and materials to support open-ended playful learning at LEGO for four years. During that time I designed learning through play activities for LEGO House, founded a small design lab called the LEGO Idea Studio, and co-led research into play and technology with MIT Media Lab, the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium, and the Reggio Children Foundation. Prior to moving to Denmark in 2015 I ran the Scratch online community as a member of the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at MIT Media Lab for 6 years. Based around the first tile-based programming language developed at MIT, the Scratch website hosted the world’s largest online programming community for children at the time.

Methodology

At the beginning of the research described here, my supervisor Sidsel Bech-Petersen and I formed the Creative Learning Research Group (CLRG)[2] consisting of myself and 5 library educators from Aarhus Public Libraries, during the Fall of 2020. The educators were selected by Bech-Petersen on the basis of availability and interest, and the selection was confirmed by the author after one on one interviews. The mission of CLRG was written in advance by the author: to grow knowledge and expertise about creative learning in libraries by studying the theory and practice of creative learning experiences, spaces, and communities, to apply these ideas to our work as library educators, and to reflect on the relevance of these ideas for libraries. For a little more than a year the CLRG group met every two weeks for 2 hour sessions, mostly online due to the closing of the library during the Covid-19 pandemic. In our meetings we discussed readings and theory related to creative learning and progressive education. Each member was invited to present some of their work outside of the CLRG to the rest of the group for critical reflection.

Creative Learning is an approach to play-based learning described by Mitchel Resnick in his book Lifelong Kindergarten (2017), which is an elaboration of Seymour Papert’s Constructionism (1993). Much of this body of work is concerned with programming and technology and is often applied in schools. Tinkering is also an elaboration of constructionism (Vossoughi, S., & Bevan, B. 2014). It was developed by the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium Science Museum and is used by non-formal educators working in environments like science museums, makerspaces, libraries, and schools around the world. Theory related to these pedagogies formed the bulk of the readings, which were selected by the author with input from the participants. Some emphasis was placed on conceptual tools designed for direct use by practitioners, for example the Learning Dimensions of Making and Tinkering produced by the Exploratorium (Bevan et al., 2014). In choosing to create an encounter between library educators and these learning theories, I was asking: Can these theories provide a shared language that is useful for reflecting on the work of creativity and learning in the library?

In addition to readings and discussions, on two occasions[3] the Creative Learning Research Group facilitated tinkering activities – one online with adults, and one in person with children and adults. In both cases, CLRG members collected Documentation in the form of photographs, videos, and notes to create a record of the learner’s encounter with the activity. Our method for collecting and reflecting on Documentation was directly inspired by the work of the children and educators of the city of Reggio Emilia in central Italy (Krechevsky et al., 2013), who over the past 80 years have developed a pedagogy known to early childhood educators around the world as the Reggio Emilia approach (Rinaldi, 2006).

The educator who practices the Reggio Emilia approach is also considered to be a researcher. Their research is about understanding and supporting the research of children. The “data” in that research consists of Documentation, which Krechevsky et al. (2013) defined as “The practice of observing, recording, interpreting and sharing through a variety of media the processes and products of learning in order to deepen and extend learning.” By reflecting critically on Documentation of children’s learning, Reggio educators develop theory to explain observations and guide their interventions. This process of critical reflection on Documentation is understood to be the engine that created (and continues to refine) the pedagogy of Reggio Emilia.

The Reggio Emilia approach takes the position that each child is unique, complex, and deeply interconnected with their surrounding culture and environment (Krechevsky et al., 2013). Reggio educators are careful to specify that any theory or understanding of learning that emerges from their own work is extremely contingent on the child’s context – including the culture of their community, school, and family (Giudici et al. 2008). What is learned may be useful in other places, but it is unwise to apply it without first reinterpreting it within the local context. As a pedagogy, the Reggio Emilia approach is committed to embracing the idiosyncratic nature of each learner and each learning community.

In designing and leading the meetings with the CLRG, I attempted to apply key ideas from this approach to the context of the library, especially with regards to collection and reflection on Documentation. Prior to each activity in which the team planned to Document the learner’s process, we began by collectively choosing a research question relevant to our discussion about theory. We then developed strategies for collecting evidence related to our question. After the activity, we spent time interpreting the Documentation we gathered together. Out of these discussions I made a draft blog post about our learnings which was then discussed and edited by various members until we reached consensus that it was finished.

In attempting to introduce reflective practice organized around Documentation to the library, my goal was to understand the following: Can we use these methods to create a context for library educators to generate interpretations and theory to explain what they have observed and documented in their practice? The reason for the experiment was to see if such a practice could become an engine for collective reflection among library educators which, over time and in the aggregate, has the potential to add up to a pedagogy of creative and playful learning in the library.

Findings

In the spirit of the Reggio Emilia approach to Documentation (Krechevsky et al. 2013), the findings section consists of brief case studies of two learning experiences facilitated by the CLRG. These were written by me with extensive input and feedback from colleagues in the CLRG, with an audience of library educators in mind. Both case studies omit information that could be used to identify the participants, but they use the facilitator’s real names (with their permission[4]). Although they describe observations of a small number of individuals, each can be thought of as representative of circumstances and people that library educators encounter frequently, and can therefore serve as foundation from which to generalize (Flyvbjerg, 2006). In addition to the documentation, each case study provides a theoretical interpretation – a “proto-theory” – that emerged out of discussions in the CLRG. The goal here is to show Documentation and interpretations of it that emerged out of a conversation among practitioners shaped by the methods described above. It is not to make rigorous claims about the evidence or interpretations about it.[5]

Case Study #1: Creative Confidence or “Handlemod” in Creative Activities

“I will probably flunk this,” said the workshop participant.

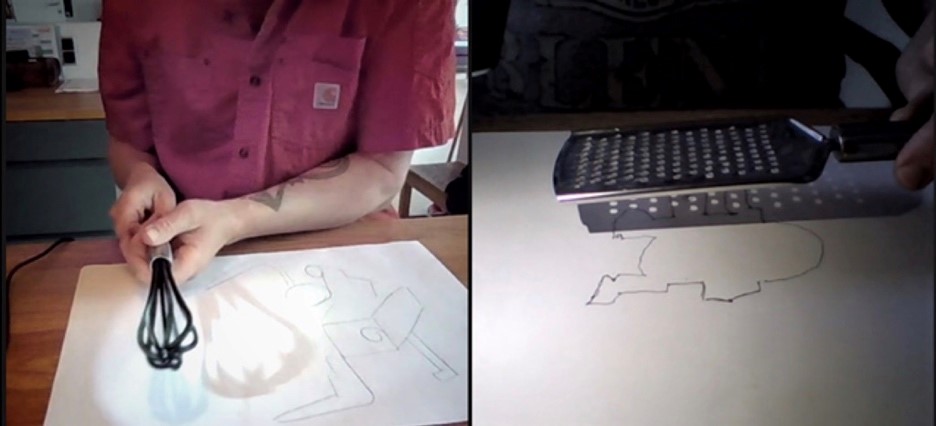

Jane, the facilitator, had just finished giving the prompt for the online tinkering activity she was facilitating to the two participants in her Zoom breakout room. Developed by the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium, Shadow Remix (Shadow Remix | Exploratorium, 2023) invites the learner to point a flashlight at something that casts a shadow, and then create a drawing that integrates and is inspired by that shadow. The participant afraid of flunking was not being ironic. He seemed genuinely afraid that he would fail.

Jane had encountered something similar many times while working as an educator in library Makerspaces. Prior to the workshop, our 5 person team of library educators called the Creative Learning Research Group had set our focus on working with people with little confidence in their own creativity. We had all encountered people like this before – mostly adults – so we made no special effort to screen participants, trusting that at least a few would fit this description. In our discussions we began to refer to the condition as low “handlemod,” a Danish word which roughly translates to “courage to act.” In our preparatory discussions prior to the beginning of the workshop, we arrived at the following research question: “How can we support people with low creative-confidence (handlemod) to help them engage meaningfully with a creative activity?”

Figure 1: Screenshot from the Shadow Remix Zoom workshop.

When invited to join a playful, open-ended activity, participants with low creative confidence tend to throw their hands up and say something to try to mitigate the expectations they are afraid will be placed on them. For example, they might say “I’m not a creative person!”

“You can’t flunk this,” Jane replies.

Jane tries to make clear that this is not a situation in which the learner will be judged or ranked on their performance. From our discussions afterward it was clear that she recognized that people who feel nervous in this way usually have little experience with the creative process, and even less confidence in it. So she begins to lend him some of her own confidence. She invites him to try to see what kind of shadow the light makes through a whisk he got from his kitchen. As he explores the different patterns formed by the shadows, she keeps up a light chatter, following along with what he is doing.

“I see the shadow looks interesting when you hold the light that way.”

“Oh, that looks nice. What if you try rotating it?”

“Why don’t you trace that line and see where it goes?”

Her speech is mostly unremarkable in terms of content and meaning conveyed, but it establishes her presence with him across the distance of the video call and helps set a casual tone. Once he has started to engage with the activity, she checks in on him periodically for the rest of the workshop.

Over the span of 30 minutes the learner gradually relaxes and becomes more and more focused on drawing and experimenting with the shadows. To an experienced facilitator of creative learning, this kind of transformation is fairly common when the right kind of support is given, though little has been written about it. It could be that having accepted the facilitator’s emphasis on play and process over outcomes, he is able to set aside the fear that prevents him from engaging playfully. Perhaps there is a role played by the aesthetics of whatever is being explored (in this case the light and shadows). From the outside, it looks like he falls in love with the process of exploring and drawing with the different shadows. It’s as if he forgets to feel afraid.

The Creative Learning Research group chose to document and reflect on the experience of working with learners with “low handlemod,” or low creative confidence, because this kind of fear is a common barrier to playful and creative learning, especially for some adults. Anyone facilitating a creative design experience for citizens will need strategies for helping some portion of them to work around their anxiety and begin to build trust in the creative process. Such strategies could be an important aspect of a pedagogy of learning and creativity for the library.

Tinkering activities are open-ended design provocations, which means the variety of possible outcomes is functionally infinite. Unlike building a birdhouse or a Lego set by following step-by-step instructions, the final product of an open-ended activity cannot be known at the beginning. It requires a willingness to explore different possibilities, reflect on feedback (both from other people and the materials themselves), and make choices about which direction to take and which new problems to pose throughout the design process. In this way, a Tinkering activity resembles a long-term design process in miniature, running at the scale of minutes instead of days, weeks, and months. Creating the conditions in which a learner can practice these skills is part of the pedagogical value of Tinkering (Petrich et al., 2013).

Case Study #2: Learning from the Facilitation Strategies of Parents and Grandparents

In November of 2021, the Creative Learning Research Group observed parents working with their children on an open-ended marble run activity in the large public area on the ramp leading to the second floor. Designed by the artist’s collective “The Secret Club” (https://schhh.net/), ‘Papalapap’ provides several open-ended provocations involving cardboard. We focused on observing and documenting families as they designed, built, and tested stackable sections of vertical marble runs. They built these using cardboard and basic crafting tools like hot glue and scissors. In preparing for the workshop, our goal was to look for indicators of creativity and self-expression as described in the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium’s Learning Dimensions of Making and Tinkering (Bevan et al., 2014). But as we discussed the notes, photos, and quotations we’d collected afterwards, we decided to refocus our reflections on the different facilitation and support strategies we observed parents and grandparents using with children.

One family we observed appeared to have parents who were very comfortable with the creative process. From the way they dressed, we thought it was likely that they work in a creative field. Having abandoned our prompt to build a marble run, their daughter instead built an ornate and sophisticated dragon with cardboard tubes, a cup, and hot glue. When she expressed uncertainty as to what sort of legs she should make for her dragon, one of her parents suggested she sketch out different possible designs on post-it notes. With the families’ permission, we collected these sketches and added them to our documentation board, which formed a shared record of what happened that day that we referred to in later discussions.

Figure 2: Photo of the dragon and the post-it note sketches for its legs.

Suggesting that their daughter sketch out different possibilities was a sophisticated facilitation move on the part of the parents. If you don’t know where to go next in a design process, it’s often useful to sketch out different ideas, and then use these sketches to reflect on which direction to take. This is a design practice that often saves resources in the long run. Investing a lot of time building legs that she later decides aren’t the right fit would be costly in terms of time and effort.

Donald Schön described something similar in his book The Reflective Practitioner (Schön, 1983). Though many people still think of creativity as a 2 step serial process of mental inspiration followed by execution, artists and creative practitioners often see that approach as expensive and potentially risky (at least at a gross scale). Picking an idea, building it to completion, and only then evaluating it (and potentially abandoning it) takes far more time and energy and involves greater risk than the more iterative approach of sketching out different possibilities and reflecting on them in order to “feel out” the right direction to take.

Though it may seem elementary to those familiar with the tenets of Design Thinking (IDEO 2015), such basic knowledge about the creative process is valuable. But not all citizens have the same level of access to it. We observed several parents who were critical of their children’s exploratory efforts, and seemed worried that the direction they took would not lead to a satisfactory outcome. Both my colleagues in Dokk1 and the designers of the Papalapap activity were careful to avoid anything in the design of the space or our facilitation strategies that would suggest that evaluation, ranking, or competition would be involved. In spite of this, some proportion of citizens tend to assume that their creations will be ranked and judged critically.

In another observation we noticed a parent who seemed particularly unsatisfied with her daughter’s exploratory efforts. At one point she took the project from her daughter’s hands and began changing it herself, explaining that what the child was doing wouldn’t work or look good. In this case, the child didn’t seem to mind and began playing with something else. She seemed mostly unphased or perhaps used to shrugging off this expression of parental anxiety.

In terms of the pedagogy of creativity, what the parent was doing in this case could be described as the opposite of what Jane was doing for the learner who was afraid of flunking the “Shadow remix” activity. Instead of lending her confidence in the creative process, she was interacting in a way that seemed more likely to instill anxiety and distrust in the creative process. As we discussed in subsequent Creative Learning Research Group meetings, this puts the facilitator in a difficult position that requires careful ethical consideration. Is it appropriate to try to constructively intervene in these situations? If so how can this be done in a way that is respectful and sensitive to both the child and the parent?

Analysis

In discussions of the documentation described above, members of the Creative Learning Research Group (CLRG) engaged in critical reflection and theory making based on evidence observed and documented together in practice. The evidence for this critical reflection lies in the interpretations, described above and below, which emerged out of those discussions. Both the concept of “handlemod,” and the discussion about techniques and guidelines for working with parents are examples of exploration of the theoretical space that have the potential to inform practice.

Generally speaking, this suggests that theory and reflective practices from the Reggio Emilia approach and constructionism can serve as a framework for a dialog between theory and practice among librarian educators. Whether or not this could eventually lead to a pedagogy of learning and play tailored for the library remains to be seen. Such an experiment would undoubtedly require a long term commitment in terms of time and resources. Below are four observations relevant to further work in this area.

Reflecting on Documentation of learning experiences leads to new questions and new ideas.

In the case study about parents and children described above, we planned to observe children’s creativity and self-expression using the Learning Dimensions of Making and Tinkering (Bevan et al., 2015). But upon further reflection, the most interesting aspects of the Documentation we gathered had to do with the relationship between adults and children. In our discussions it became clear that this is a particularly rich and interesting area for librarian educators to explore, since libraries welcome interaction within families and across generations in ways that schools do not.

Our reflective discussions afterwards surfaced several interesting and important issues for further consideration. Is it appropriate, ethically speaking, to intervene in family dynamics that seem likely to limit the child’s learning experience? For example, if we see a father grab the cardboard project out of his child’s hands while judging it in a negative light, can we try to constructively intervene? How can we use our authority as educators to effectively communicate our pedagogical values to parents? If we can better articulate our vision of what quality in creative learning in the library looks like to them, will it help us to engage them as allies?

Out of this conversation, one member proposed that we create a “Dogma” – a collection of rules and constraints that frame the work we’re doing in creative spaces in the library. We also debated possible slogans to place on the walls of an activity space which we could refer parents to when they enter, as a means of setting the frame for the type of playful creativity we hope to see. None of these made it past the draft stage before the CLRG group ended shortly after. But they suggest that a process of reflective documentation has the potential to lead to innovative ideas in the form of both new problems to solve and new solutions to solving them. Explored systematically, such ideas could form the basis for further practical and theoretical insights.

The Librarian educators observed already used a patchwork of ideas from various learning theories, but they rarely had space and time to reflect on them.

In the process of working with the Creative Learning research group I made notes and observations in order to be able to reflect critically on the goal of understanding what it would take to develop a pedagogy of creativity and learning in the library. From these observations, it was clear that each of my colleagues in the CLRG already had a good deal of knowledge built from experience facilitating creative learning. To name one example, Jane’s ability to soothe and support the learner who was afraid of flunking was perhaps “primed” by the discussions we had about “handlemod” and creative confidence prior to the workshop. But she had already intervened in this way many times before.

But while Jane had already developed these skills and insights on her own, she mentioned that she had never discussed them with any of her colleagues. Prior to joining the CLRG, she was busy with numerous projects and had little time for individual reflection and even less for reflecting with peers on pedagogical questions. So while she knew how to work with people who lack creative confidence, there was no shared language with which to discuss or refine these ideas with colleagues. By “shared language,” I mean a collection of concepts that experts in a field use to discuss and reflect together on subtle issues associated with their craft.

As we discussed the concept of creative confidence in English, we debated how best to express it in Danish. Danish is the first language of all members the CLRG group except for me, an American, and at the time I had very little understanding of Danish. So part of developing a shared language for use in a Danish library involved choosing the right Danish word to represent the concept we were discussing in English. The group explored different options, including “kreativ selvtillid” (creative self-confidence) and “handlemod” (courage to act) – finally settling on the latter.[6] In this case the choice of words for translation was an explicit and literal form of creating or defining a shared language, a building block for pedagogical theory.

In our ongoing discussions about creative confidence and how to constructively intervene to support its development in learners, a member of CLRG whose work is focused on children and crafting had a lot to contribute. She described a variety of different strategies she used to help children who were nervous or otherwise self-critical about their crafting abilities. As with Jane, she had an expertise developed over years which she rarely discussed with colleagues. Mostly this was due to lack of time and context for such discussions, but also perhaps due to the lack of a shared language with which to do it.

CLRG was composed of library educators from two organizationally distinct departments: adult learning and children’s learning. This meant that there was less opportunity for shared reflection between members of different departments than there was within each department itself. At least in the realm of hands-on creative learning, the consensus seemed to be that there was more overlap in terms of useful knowledge across those working in different age ranges than most had initially imagined. In our small but developing pedagogical conversations, educators working with children had a lot more in common with adult educators than either initially imagined.

Time for reflection, it was universally acknowledged by members of the CLRG, is the first thing that gets sacrificed when the schedule gets tight. And the schedule is usually tight. It is easy to assume that this is because of the demands of management — and surely in many cases it probably is — although this did not seem to be the case in our situation. In the CLRG team there was recognition that time for reflection was sometimes sacrificed by the library educators themselves, some of whom mentioned they often underestimated time costs and took on too much out of a desire to get involved in interesting or exciting projects. But the recognition that most projects were evaluated by politicians who are more interested in the number of participants than the quality of their learning experiences also seemed to play a role.

In general, much of the time, effort, and attention of many library educators appears to be structured and funded by grants. In the absence of a commitment from leadership to developing a distinct pedagogical stance, it’s difficult to imagine a coherent pedagogy of learning and creativity in the library emerging by itself.

Proposing theory in the form of explanations of Documentation requires a firm epistemic stance.

In our discussions, I was most active in proposing explanations and theories to try to explain what we had observed and documented. Partly this was intentional in that I wanted to see if others would follow my example and assert explanations for what they observed. While there were elements of interpretation from all participants in our discussions, only one member attempted to apply this approach to her work outside of the CLRG group. This led to the creation of a set of pedagogical guidelines by the IRIS team, a project that focuses on developing new opportunities for technological literacy. They used these to frame their ongoing work with children.

There could be many personal and cultural reasons for what felt to me like a reluctance to assert new explanations to explain observations from practice. One explanation is that my librarian educator colleagues see themselves as “only” practitioners, and not academic researchers. Therefore, proposing explanations for what they observe is not in their job descriptions, which tend to focus more on actions than interpretations. There appeared to be a readiness to defer to formal and experimental research, even though there was also skepticism about its relevance to their work. Here I found a somewhat paradoxical situation: They had great respect for academic research which, by their own admission, was almost never relevant or useful to them as practitioners. It is possible that this willingness to defer to the expertise of academia accounts for some of their hesitancy to propose their own theories about what they observed in their work.

Carla Rinaldi, professor, author, and advocate for the Reggio Emilia approach to education, has written and spoken about the relationship between theory and practice in ways that are relevant to these epistemic challenges.

Theory and practice should be in dialogue, two languages expressing our effort to understand the meaning of life. When you think, it’s practice; and when you practice, it’s theory. ‘Practitioner’ is not a wrong definition of the teacher. But it’s wrong that they are not also seen as theorists. Instead it is always the university academics that do theories, and the teachers…they are the first to be convinced of it. In fact, when you invite them to think or to express their own opinions, they are not allowed to have an opinion. (Rinaldi, 2006)

She goes on to suggest an alternative:

It’s not that we don’t recognise your [academic] research, but we want our research, as teachers, to be recognised. And to recognise research as a way of thinking, of approaching life, of negotiating, of documenting. It’s all research. It’s also a context that allows dialogue. Dialogue generates research, research generates dialogue. (Rinaldi, 2006)

My own view, which I shared with colleagues in CLRG, is that no academic researcher in the university has access to the wealth of contextual knowledge that library educators are swimming in. The fact that they are in situ, engaging with the work of facilitating learning in a context that differs fundamentally from that of schools, makes them the best equipped to propose explanations for the things that they observe. These explanations are the precursors of theory.

If the reluctance I observed is explained by Rinaldi’s description of the hierarchical relationship between practitioners and academics, then it presents a significant challenge to the goal of developing a pedagogy of the library. For such a pedagogy to develop, practitioners must assert that their insights are worthy of consideration – both by other practitioners and by academics in related fields. They then must be described, shared, and discussed with other practitioners and researchers, again and again, over the course of years. This would require practitioners to take an epistemic stance that asserts both the value of their local, experience-based knowledge and their right and ability to generate theory to explain it. But my interlocutors seem to believe that the value of generalized academic knowledge about human learning far outweighs any potential contribution of their own. This is in spite of my impression that most would be hard pressed to think of even a single practical insight from the world of academic research on learning from the past few decades.

In the absence of a shared definition of quality in learning experiences, it’s difficult to know where to begin.

Learning is incredibly complex and difficult to measure – especially when it is improvisational and creative (Resnick, 2017). Developing a pedagogy that explains how to design and facilitate towards it is a difficult undertaking. It benefits from at least some initial agreement as to what quality learning experiences look like in order to sustain movement towards that goal.

My impression was that there was a good deal of agreement about quality learning in the Creative Learning Research Group, much of which stemmed from their shared culture. Danish educational values are a cherished part of the Danish cultural heritage. But when I inquired in greater detail as to how these values could be enacted, answers tended to be somewhat general and difficult to base clear actions upon. It wasn’t always clear what the expression of those values in a real learning experience would look like. At one point, one member of the group stated that while there was general cultural agreement at the level of values about learning, he felt that the practice of education in Denmark didn’t always live up to those values. I had hoped that Documentation, because it provokes a conversation between theory and evidence gleaned from practice, might help to concretize what these values do or do not look like in action, but I don’t think we reached that level. It may be something that can only emerge from repeated iterations of facilitating activities and reflecting on them.

Like cultural institutions worldwide, libraries in Denmark are evaluated by how many citizens make use of them. There is a risk that in the absence of a clearly articulated definition of quality learning, “the numbers” of people who show up for a given activity will be viewed as the primary measure of success. But as is true in schools, the number of participants who attend something, even when they have the freedom to choose whether they will attend it, is not in itself a good indicator of learning.

Reflective documentation could be a means for describing what quality learning looks like in the library – both for other educators and for outside stakeholders. But a clearer description or set of examples showing what quality learning in a library looks like would help to calibrate the compass such that library-educators could work towards a specific direction, as well as try to address the problem of how best to gather evidence relevant to that goal.

Discussion

Generally speaking, each citizen’s use of the library is unique. Learning in a library tends to be non-linear and idiosyncratic: A child checks out a dinosaur book, an engineer looks for a reference on a manufacturing process, etc. While the structure of school asks learners to have the same or similar experiences, the goal of the library is to support the learner in having whatever experience is meaningful to them at that moment. Rather than following a pre-defined path, the learner arrives seeking to understand something relevant to their own interests, interests which may evolve and change even during the course of their visit.

Libraries often collaborate constructively with schools. But the fact that most people identify learning as something that mostly happens in school makes this relationship potentially risky for libraries. As Gopnik (2011, in Björneborn, 2017) puts it, “Adults often assume that most learning is the result of teaching and that exploratory, spontaneous learning is unusual. But actually, spontaneous learning is more fundamental.” For some, learning in the library may be seen as an accessory to learning in school, where “real” learning happens. Without a clear articulation of its own distinct learning goals, values, and pedagogy, the library risks becoming irrelevant in the popular conception of learning. The position of libraries is made more precarious by the digital age, which renders at least one of its previous functions – the warehousing of physical books – obsolete.

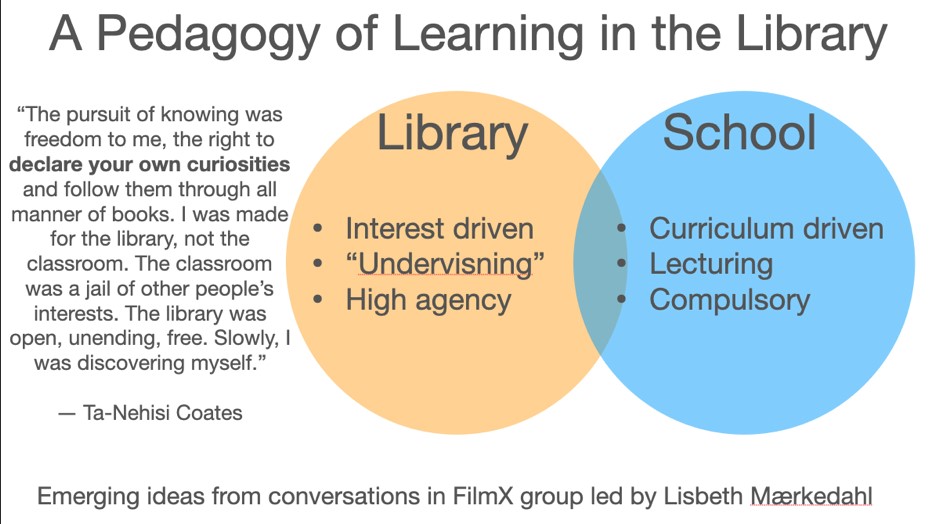

In the course of discussions with colleagues from the IRIS (formerly Film X) project in Aarhus Public libraries, I created a Venn diagram to describe a way to think about the relationship between learning in libraries and schools. To varying degrees, schools around the world tend to be curriculum driven, compulsory, and dependent on lecturing to achieve the goal of information transfer and successful recall in students. Learning in the library is largely interest-driven, so the learners have a high degree of agency and freedom to choose and shape their own experience. In our discussion one librarian educator pointed out that the literal translation of the Danish word for teaching – undervisning – is “showing wonders.” She suggested that this would be a good way of framing the role of library educators interested in facilitating creative explorations of STEM phenomena. Another referenced a quote by the famous American intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates which describes his affection for the library and criticism of school.

Figure 3: Venn diagram that emerged out of discussions with the IRIS group (formerly FilmX).

This is not to say that the library should try to replace or actively criticize schools, or that schools are never interested in things like agency and interest-driven learning. Many schools share similar goals and aspirations which I attribute in this diagram to libraries. The specific content is tentative, and less important than the structural idea of the Venn diagram as a means of framing (and shaping) a relationship between two different institutions. If a library articulates a clear stance about the kind of learning it values, then it can recognize where that kind of learning does and does not overlap with the school’s agenda. It can use this to shape its interactions with schools to grow and develop in whatever way it wishes to.

To give an example based on the cursory bullet-points shown in the slide, if the school would like to collaborate with the library on an open-ended programming activity in which children can design their own games based on their interests, the library would respond with an enthusiastic “yes!” Such an activity falls clearly into the shaded area where the pedagogical values of the school and the library overlap. It also presents an opportunity for the library to develop its own educator’s expertise in an area aligned with its pedagogical goals. But if the school invites the library to assist with rote memorization of vocabulary terms to satisfy requirements of the curriculum that don’t connect meaningfully to children’s interests, the library (in this example) should politely decline.

In order to make possible a productive dialogue between theory and practice, libraries must make choices about the kind of learning they will or will not focus on developing their capacity to support. Just as no one can become an expert in everything, no library can hope to develop expertise in every pedagogical approach. Expertise takes time and focus to develop, and this requires that practitioners have a clear view of the kinds of learning they are cultivating and the kinds of learning they are not cultivating. Libraries need to create an institutional identity around learning that citizens can recognize as both distinct from schools and valuable in its own right. Failure means being seen as merely an “accessory” to school learning, and accessories are the first to go when times get tough.

Conclusion

The claims of this research must be limited, as it reflects impressions formed from working with a small group of library educators in a well-known and well-resourced library. Most librarian educators would likely encounter much greater challenges doing this work in their libraries, many of which have little to no budget for running learning activities. Still, I hope that at least some of the ideas here could be useful to librarian educators in diverse contexts.

Any reflective dialog between theory and practice that is to yield useful insights for practitioners will take a significant amount of time and energy. The approach to Documentation as developed in the Reggio Emilia tradition, when reinterpreted in the library, is one viable means for organizing an ongoing conversation that meets Weick’s (1989) definition of a theory making process “designed to highlight relationships, connections, and interdependencies in the phenomenon of interest.” Organizing teams around pedagogical focus, rather than age of the library patrons or other categories, could be another way to help facilitate such a conversation. Inviting library educators into a dialog about what the library sees as a quality learning experience, and providing concrete examples, is another.

Many more questions remain open. What sort of rhythm and proportion would be most effective for supporting library educators in encountering and digesting existing pedagogy, documenting in-person practice, and reflecting on documentation afterwards? Should one spend a few hours per day on each topic successively each week? My own attempts at asking this question were foiled by the uncertainty and interruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic.

It seems probable that an effective pedagogy for libraries would have to be developed in a conversation among library educators that extends beyond any single library or library system. What would be the best medium for sharing insights and ideas about creativity and learning across libraries around the world? Many of the librarian educators I’ve encountered don’t read much theory or keep up with the latest research. This might be because they don’t often find things to read that are relevant and meaningful to their work as practitioners. What medium would be the right medium through which to have an ongoing conversation as research practitioners, and not just practitioners? What sort of network would be able to support this kind of ongoing conversation, and help to justify the time and expense associated with it?

As Jochumsen et al. (2012) recognized, open-ended creativity and playful, interest-driven learning can be incredibly engaging for citizens of all ages. In my view, this is due to the improvisational, open-ended, and joyful nature of play. What gets created depends on the unique ideas and interests of the people who show up. But designing and facilitating this kind of playful learning is challenging. This is why educators working in this area benefit from an ongoing reflective conversation with their peers.

Acknowledgements

Many of the ideas presented come from extensive discussions with library educators in Aarhus Public Libraries, especially the Creative Learning Research Group, which included Sofie Gad, Rasmus Ott, Marie Pasgaard Ravn, Jane Kunze and Lisbeth Mærkedahl.

Many thanks to my advisors for their help and patience, including Andreas Roepstorff, Sidsel Bech-Petersen, and Peter Dalsgaard. Thanks to Klaus Thestrup and Lennart Björneborn for thoughtful feedback.

Thanks to the Carlsberg Foundation and Aarhus Public Libraries for making this research possible.

Notes

[1] In this article a library educator is defined as anyone who designs or facilitates in-person learning experiences. A learner is anyone interacting with them or a learning experience they have designed.

[2] Description of the Creative Learning Research Group at Dokk1 Library: https://www.aakb.dk/nyheder/kort-nyt/the-creative-learning-research-group-at-aaarhus-public-libraries

[3] Our original plan was for the Creative Learning Research Group to co-design and co-facilitate between 6 and 10 hands-on tinkering workshops which we could observe, Document, and reflect on together, allowing for a much larger pool of data from which to theorize. The lockdowns and restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic forced us to spend much more time reading and discussing theory and much less time running workshops and reflecting on Documentation.

[4] I chose to use facilitator’s real names out of a concern that anonymity without a compelling reason reinforces the idea that the unique qualities and interests of different learners and teachers don’t matter, and a facilitator is just a facilitator and a learner is just a learner. Every good facilitator I’ve known has their own way of doing things, just like every good learner has their own idiosyncratic approach to learning.

[5] While strong claims can be based on evidence from case studies (Welch et al. 2011), we would need to have run these activities many more times than we were able to in order to generate sufficient observational data to make a serious claim to rigor. That was not the goal of this research, which was focused mainly on experimenting with processes that could support theory making of the sort that could eventually lead to the establishment of a pedagogy.

[6] It’s worth noting here an interesting cross-cultural issue. The English “creative confidence,” as heard by Danish CLRG members, would be something one would attribute almost exclusively to geniuses or well-established artists like Picasso. Whereas “Handlemod” could be understood as a quality anyone would possess to varying degrees, and which could be more or less supported by different actions on the part of the facilitator.

References

Bateson, G. (2002). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Cresskill, NJ. Hampton Press, p. 141.

Bevan, B., Petrich, M., & Wilkinson, K. (2014). TINKERING Is Serious PLAY. Educational Leadership, 72(4), 28–33.

Bevan, B., Gutwill, J. P., Petrich, M., & Wilkinson, K. (2015). Learning Through STEM-Rich Tinkering: Findings From a Jointly Negotiated Research Project Taken Up in Practice. Science Education, 99(1), 98–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21151

Björneborn, L. (2017). Three key affordances for serendipity: Toward a framework connecting environmental and personal factors in serendipitous encounters. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 1053–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2016-0097

Dewey, J. (2015). Experience and education (First free press edition 2015). Free Press.

Dumit, J. (2014). Plastic neuroscience: Studying what the brain cares about. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00176

Einarsson, Á. M., & Hertzum, M. (2020). How is learning scaffolded in library makerspaces? International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 26, 100199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2020.100199

Eisenhardt, K. M., Graebner, M. E., & Sonenshein, S. (2016). Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1113–1123. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4004

Giudici, C., Barchi, P., & Harvard Project Zero (Eds.). (2008). Making learning visible: Children as individual and group learners ; RE PZ (4. printing). Reggio Children.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Gray, P. (2010). The Decline of Play and Rise in Children’s Mental Disorders | Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/freedom-learn/201001/the-decline-play-and-rise-in-childrens-mental-disorders

Gopnik, A. (2011). “Why preschool shouldn’t be like school”, Slate, November 16, available at: http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2011/03/why_preschool_shouldnt_be_like_school.html (accessed 9 August).

IDEO. (2015). Design Thinking for Libraries: A Toolkit for Patron Centered Design. IDEO. http://designthinkingforlibraries.com/

Jochumsen, H., Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C., & Skot-Hansen, D. (2012). The four spaces – a new model for the public library. New Library World, 113 (11/12), 586–597.

Kohn, A. (1999). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton Mifflin Co.

Krechevsky, M., Mardell, B., Rivard, M., & Wilson, D. G. (2013). Visible learners: Promoting Reggio-inspired approaches in all schools. Jossey-Bass.

Montgomery, M. (2015). Pedagogy for Practical Library Instruction: What Do We ‘Really’ Need to Know? Communications in Information Literacy, 9(1), 5.

Olson, K. (2009). Wounded by school: Recapturing the joy in learning and standing up to old school culture. Teachers College Press.

Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. BasicBooks.

Pedagogy. (2022). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pedagogy&oldid=1105947430

Petrich, M., Wilkinson, K., & Bevan, B. (2013). It looks like fun, but are they learning? In M. Honey & D. Kanter (Eds.), Design, make, play: Growing the next generation of STEM innovators. Routledge.

Rasmussen, C.H. (2016). The participatory public library: The Nordic experience. New Library World, 117(9/10), 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-04-2016-0031

Resnick, M. (2017). Lifelong kindergarten cultivating creativity through projects, passion, peers, and play. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11017.001.0001

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning.

Robinson, S. K. (2010). Sir Ken Robinson: Changing education paradigms | TED Talk. Retrieved 6 August 2022, from https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_changing_education_paradigms

Rogers, A. (2014). The base of the iceberg: Informal learning and its impact on formal and non-formal learning. Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Shadow Remix | Exploratorium. (2023, April 15). https://www.exploratorium.edu/tinkering/projects/shadow-remix

Vossoughi, S., & Bevan, B. (2014). Making and Tinkering: A Review of the Literature. National Research Council Committee on Out of School Time STEM, 57.

Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory Construction as Disciplined Imagination. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 516. https://doi.org/10.2307/258556

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 740–762. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.55

Willingham, T., & DeBoer, J. (2015). Makerspaces in libraries. Rowman & Littlefield.

Østergård, M. (2019). Dokk1 – Re-inventing Space Praxis: A Mash-up Library, a Democratic Space, a City Lounge or a Space for Diversity? In D. Koen, T. E. Lesneski, & International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (Eds.), Library design for the 21st century: Collaborative strategies to ensure success. De Gruyter.